French inventor, Joseph Nicéphore Niepce was born today, March 7, 1765 in Chalon-sur-Saône, Saône-et-Loire, where his father was a wealthy lawyer. He had an older brother Claude, a sister, and a younger brother, Bernard.

He created the first true photographs, but with the help of his brother, Claude, he also invented the first internal combustion engine.

Niépce was educated for the Catholic Priesthood. While studying at the seminary, he decided to adopt the name Nicéphore in honor of Saint Nicephorus the ninth-century Patriarch of Constantinople.

At the seminary, his studies taught him experimental methods in science, and by practicing those, he rapidly achieved success and ultimately graduated to become a professor at the college.

Because his family was suspected of royalist sympathies, Niépce fled the French Revolution but returned to serve in the French army as a staff officer under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1791 and served a number of years in Italy and on the island of Sardinia, until he contracted typhoid fever in 1794.

He retired to Nice, where he married and married Agnes Romero, became active in local politics as the Administrator of the Nice district. But only a year later, Niépce resigned.

In 1801, he settled near his native town of Chalon-sur-Saône, along with his brother Claude to continue their scientific research, and be reunited with their mother, their sister and their younger brother Bernard.

Here, they managed the family estate as independently wealthy gentlemen-farmers, raising beets and producing sugar.

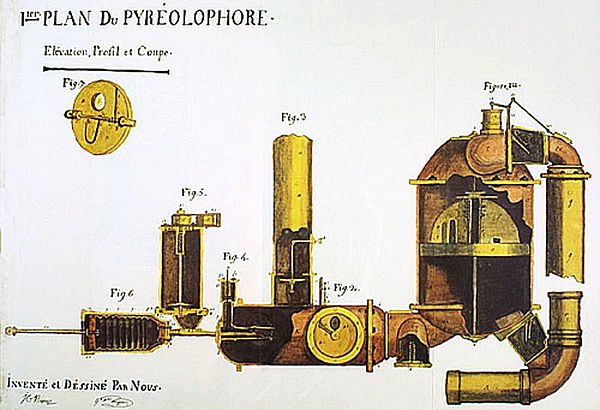

With the help of his family fortune, Niépce experimented independently. In 1807, he and Claude invented the world's first internal combustion engine, that they named, “The Pyréolophore,” explaining that the word was derived from a combination of the Greek words for “fire,” “wind,” and “I produce.”

The engine ran on controlled dust explosions of lycopodium powder and was installed on a boat that ran on the river Saône.

Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte ultimately granted them a patent that same year after he was shown its ability to power a boat upstream on a river in France.

If that wasn’t enough, ten years later, the brothers were the first in the world to make an engine work with a fuel injection system.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce wasn’t finished. In the 1820s, he’d become fascinated with the printing method of lithography, in which images drawn on stone could be reproduced using oil-based ink.

Around 1825, searching for other ways to produce images, from a high studio window of his estate, Le Gras, in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, France, Niépce set up a device called a camera obscura, which captured and projected scenes illuminated by sunlight, and he trained it on the view outside—of the buildings and surrounding countryside.

Niépce knew a very long exposure in the camera was required. With sunlight striking the buildings on opposite sides, the exposure lasted a minimum of eight hours, but a researcher who later studied Niépce's notes and recreated his processes found that the exposure must have continued for several days.

The scene was cast on a treated pewter plate that, after many hours, retained a crude copy of the buildings and rooftops outside.

Niépce called it heliography, which literally means "sun drawing.”

It had taken him over twenty years of experimenting with optical images before he had this success. It remains the the first known permanent photograph of a real-world scene.

Once Niépce had the success he desired, he decided to travel to England to try to promote his new invention to the Royal Society. Unfortunately, he was met with rejection. The Society’s rule stated that it would not promote any discovery with an undisclosed secret. Niépce was not prepared to share his secrets with the world, so he returned to France disappointed that he was unable to make a success of his new invention.

In 1828, his brother, Claude died half-mad and destitute in England, having squandered the family wealth chasing inappropriate business opportunities

it was recommended to Niepce that he meet with Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre, a painter of theater scenes, to discuss his invention. In 1829, Niepce and Daguerre became partners. Together, they developed the physautotype, an improved process that used lavender oil distillate as the photosensitive substance.

Niépce entered into a partnership with Louis Daguerre, who was also seeking a means of creating permanent photographic images with a camera.

Niépce died suddenly in 1833, due to a stroke at the age of 68, financially ruined—so much so that even his grave in the cemetery of Saint-Loup de Varennes was financed by the municipality. The cemetery is near the family house where he had experimented and had made the world's first photographic image.

Daguerre continued to experiment, eventually working out a process that only superficially resembled Niépce's, but greatly reduced the exposure time, and created sharper (“Daguerreotype”) images— photography’s next major advancement.

For many years, Niépce was largely ignored, and received little credit for his contribution. Later historians have reclaimed Niépce from relative obscurity, and it is now generally recognized that his "heliography" was the first successful example of what we now call "photography"

View from the Window at Le Gras and other images created by Niépce were occasionally exhibited as historical curiosities. View from the Window at Le Gras was last publicly shown in 1905 and then fell into oblivion for nearly fifty years.

It’s no overstatement to say that Niépce’s achievement laid the groundwork for the development of photography.

While many inventive men had experimented with the photograph, solving the mystery of fixing the camera image had eluded them until the success of Joseph Nicephore Niepce.

In honor of Niépce, The Niépce Prize was created and has been awarded annually since 1955 to a professional photographer who has lived and worked in France for over 3 years.

In 2003, Life listed View from the Window at Le Gras among 100 Photographs that Changed the World.