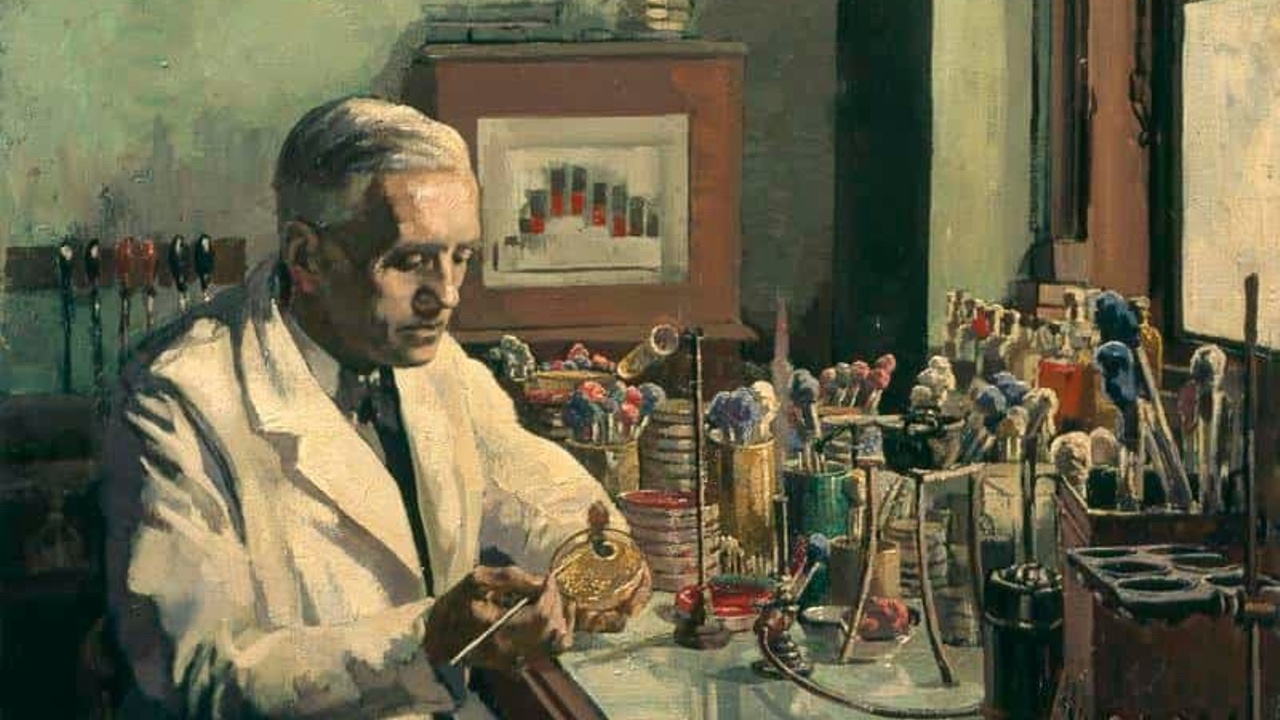

The Son of a Scottish Pig Farmer who may have Saved Your Life...

His name was Alexander Fleming—the son of a Scottish pig farmer. He served in World War I, and his research has likely saved your life at some point. Or at least your parents' or grandparents' lives--and therefore yours as well! He received the Nobel Prize for his accidental discovery of penicillin.

Because he passed away On this Day, March 11, 1955, now is a very good time to recount his incredible story...

Sir Alexander Fleming was born at Lochfield near Darvel in Ayrshire, Scotland on August 6th, 1881.

His parents, Hugh and Grace were farmers, and Alexander was one of their four children. He also had four half-siblings who were the surviving children from his father Hugh's first marriage.

His parents could not afford to send him to school. His father passed away when he was only seven years of age.

He worked at a shipping office in London where he moved to when he was 13, and ultimately attended the Royal Polytechnic Institution since he could not afford to go to a private university.

His early education was spent at Louden Moor School, Darvel School and finally Kilmarnock Academy where he had earned a two year scholarship. He was a member of the Territorial Army from 1900 to 1914 as a private in the London Scottish Regiment.

After some time, he inherited some money from an uncle who passed away and he was able to enroll at St Mary’s Hospital Medical School--where he graduated with an MBBS Degree in 1906, and later with an MSC in Bacteriology in 1908. While at St. Mary's, he won the 1908 gold medal as the top medical student.

He was able to continue his studies throughout his military career and on demobilization he settled to work on antibacterial substances which would not be toxic to animal tissues.

After his initial education in Scotland he moved to London to live with his older brother, Thomas Fleming, and where he attended the Polytechnic. He spent four years in a shipping office before entering St. Mary’s Medical School, London University.

In 1915, while Fleming was establishing a career for himself, he married Sarah Marion McElroy, an Irish woman who worked as a nurse. They had a son Robert, born in 1924 who would later follow in his father’s footsteps and practice medicine.

Until the outbreak of the First World War Fleming established a private practice, specialising in the treatment of venereal diseases, becoming one of the first in Britain to use a new drug that proved effective in treating syphilis.

Fleming would go on to serve as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War I. With his impressive credentials, his assistance was needed on the battlefield and so Fleming, along with many of his peers worked at the Western Front in France in the battlefield hospitals. He worked as a bacteriologist in a makeshift lab in Boulogne in France, studying wound infections.

While working there, Fleming devised an experiment that explained why the application of antiseptics was doing more harm than good, as their diminishing effects on the body's immunity agents largely outweighed their ability to break down harmful bacteria — therefore, more soldiers were dying from antiseptic treatment than from the infections they were trying to destroy.

He explained that antiseptics tackled the problem only superficially but did not work for deep wounds infected with bacteria.

Fleming recommended that, for more effective healing, wounds simply be kept dry and clean. However, his recommendations largely went unheeded, and the majority of medical officers continued to treat their patients using the traditional methods.

In 1918, after the war, he returned to St.Mary’s. There, he discovered lysozyme in 1921 and although it was only effective on some bacteria, it was an important medical breakthrough nonetheless.

Eight years later Fleming would make his most famous discovery, although in accidental, unplanned circumstances during his work on the influenza virus.

Fleming kept a messy lab. He left petri dishes, microbes and nearly everything else higgledy-piggledy on his lab benches, untended. One day in September of 1928, Fleming returned to his laboratory after spending some time away in August with his family.

There, he found mold had grown on a staphylococcus culture plate and formed a bacteria barrier around it. The bacteria immediately surrounding the fungus had been destroyed.

When he noticed that plate, he famously said, “Well, that’s funny….”

The circle of mold was a fungus. And in that chance moment, Fleming discovered the antibiotic properties of an antibiotic that would change the world.

Fleming observed that the mould culture prevented the growth of this bacteria, even when diluted. Fleming had just discovered an antibiotic, and at first, he called this “mold juice.” The world’s first antibiotic had been discovered.

By 1929, he had personally named his discovery “penicillin,” revolutionizing medical science for all future generations.

Ultimately, penicillin’s powerful anti-bacterial effects were discovered to be effective on many hard-to-treat organisms such as the pathogens which caused pneumonia, meningitis, scarlet fever and also gonorrhea.

Fleming would go on to publish his observations, however it would fail to gain much attention and after some setbacks in the mass production of penicillin, Fleming turned his attentions to other areas of work.

He was elected Professor of the School in 1928 and Emeritus Professor of Bacteriology, University of London in 1948. He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1943, and was knighted in 1944, Sir Alexander Fleming—an important acknowledgement for his scientific achievements.

“Penicillin sat on a shelf for ten years,” Fleming would later say, “while I was called a quack.” And yet, Fleming persisted—he kept, grew, and distributed the original mould for twelve years, and continued until 1940 to try to get help from any chemist who had enough skill to make penicillin to mass produce it, without success.

Finally, two men, Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain, came up with the funds and research to start mass production, just in time for the Second World War and the treatment of wounded soldiers. American manufacturing firms and pharmaceutical companies began tackling the large-scale production of penicillin.

By D-Day, June 6, 1944, enough penicillin had been produced to treat all the wounded Allied troops.

Fleming’s career flourished, but he was modest about his part in the development of penicillin, describing his fame as the "Fleming Myth" and he praised other close associates for transforming his laboratory curiosity into a practical drug. “Nature makes penicillin,” Fleming would say. “I just found it.”

Alexander Fleming was awarded the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly with Ernst Boris Chain and Sir Howard Walter Florey "for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases."

By 1953, Sir Alexander Fleming had married again to a fellow doctor working for St Mary’s and lived a further two years, dying in March 1955.

Fleming’s wife died in 1949, and he married again in 1953. His second wife was Dr. Amalia Koutsouri-Voureka, who was a Greek colleague at St. Mary’s.

Sir Alexander Fleming died two years later, on March 11, 1955, and is buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The discovery of penicillin and its development as a prescription drug marked the start of modern antibiotics.

Fleming’s legacy changed the practice of medicine for future generations and saved countless lives. Sir Alexander Fleming’s career and discoveries will be celebrated and acknowledged for centuries to come.

In 1999, he was named among Time magazine's list of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th century.

#OTD #History #pharma #pharmaceuticals #WW1 #WW2 #penicillin #leaders#leadership