King Tutankhamen

Feb 21, 2021

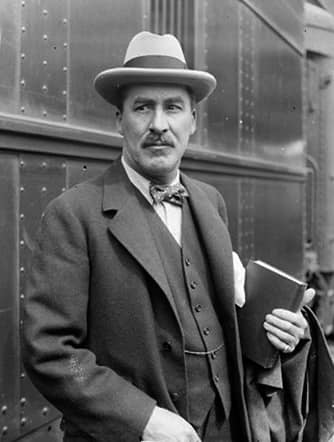

On February 16, 1923, in Thebes, Egypt, English archaeologist Howard Carter entered the sealed burial chamber of the ancient Egyptian ruler King Tutankhamen.

Because the ancient Egyptians saw their pharaohs as gods, they carefully preserved their bodies after death, burying them in elaborate tombs containing rich treasures to accompany the rulers into the afterlife.

After the pharaoh died, his remains were carried down into a tomb west of the Upper Nile, in the vast royal necropolis known as the Valley of the Kings. So, too, were all manner of mementos and goods from Tutankhamun’s life: disassembled chariots, a childhood gaming board, furniture, lamps, sculpture, weapons, jewelry. The tomb, a mini-labyrinth of tunnels, chambers, and blocked passageways, was sealed. Tutankhamun’s followers had done what they could to equip the pharaoh for a safe journey through the underworld to a joyful afterlife.

In the 19th century, archeologists from all over the world flocked to Egypt, where they uncovered a number of these tombs. Many had long ago been broken into by robbers and stripped of their riches.

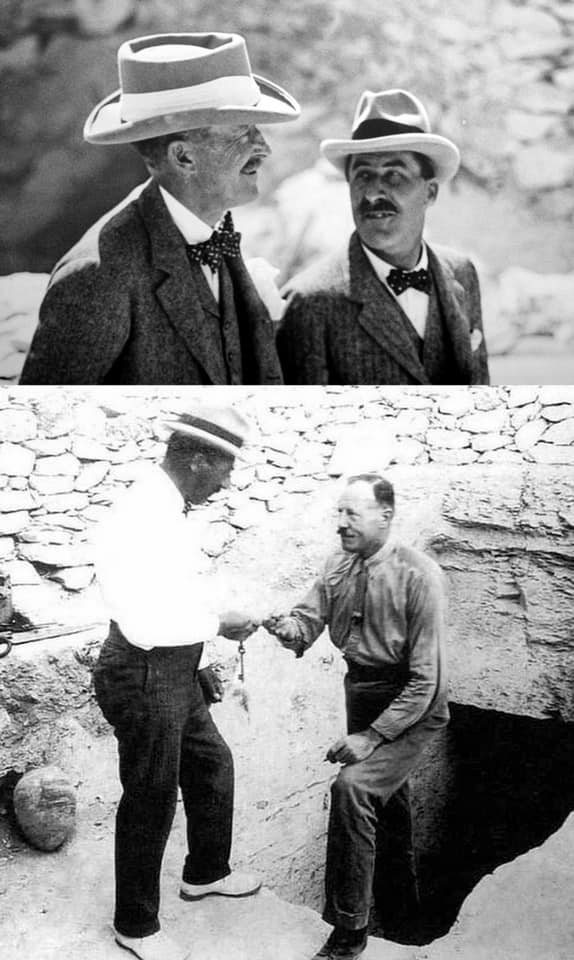

When Carter arrived in Egypt in 1891, he became convinced there was at least one undiscovered tomb–that of the little known Tutankhamen, or King Tut, who lived around 1400 B.C. and died when he was still a teenager. Backed by a rich Brit, Lord Carnarvon, Carter searched for five years without success. In early 1922, Lord Carnarvon wanted to call off the search, but Carter convinced him to hold on one more year.

In November 1922, the wait paid off, when Carter’s team found steps hidden in the debris near the entrance of another tomb. The steps led to an ancient sealed doorway bearing the name Tutankhamen. When Carter and Lord Carnarvon entered the tomb’s interior chambers on November 26, they were thrilled to find it virtually intact, with its treasures untouched after more than 3,000 years. The men began exploring the four rooms of the tomb, and on February 16, 1923, under the watchful eyes of a number of important officials, Carter opened the door to the last chamber.

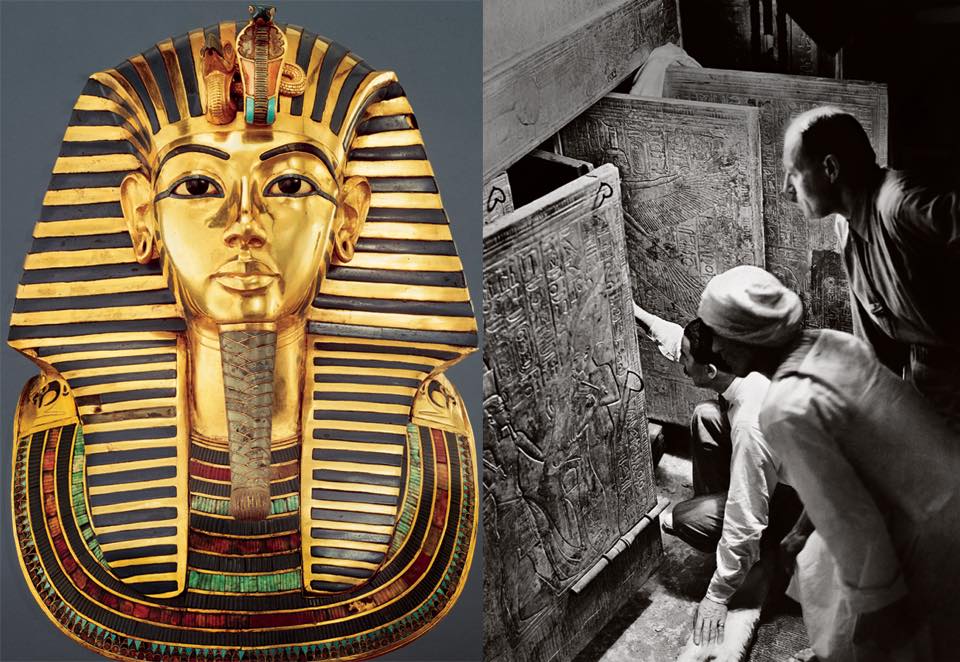

Inside lay a sarcophagus with three coffins nested inside one another. The last coffin, made of solid gold, contained the mummified body of King Tut. Among the riches found in the tomb–golden shrines, jewelry, statues, a chariot, weapons, clothing–the perfectly preserved mummy was the most valuable, as it was the first one ever to be discovered.

Despite rumors that a curse would befall anyone who disturbed the tomb, its treasures were carefully catalogued, removed and included in a famous traveling exhibition called the “Treasures of Tutankhamen.”

Several weeks after discovering the tomb, Carter and Lord Carnarvon, who financed the excavation, looked into the tomb. Lord Carnarvon died five months later due to an infected mosquito bite, leading many to speculate, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, that his death was caused by protections created by Tutankhamen's priests to guard the royal tomb.

The curse, it was believed, did not differentiate between thieves and archaeologists, causing bad luck, illness, or death to anyone who disturbed the mummy. A study conducted showed that of the 58 people who were present when the tomb and sarcophagus were opened, only eight died within 12 years. The last survivor died 39 years after the event.

The exhibition’s permanent home is the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.