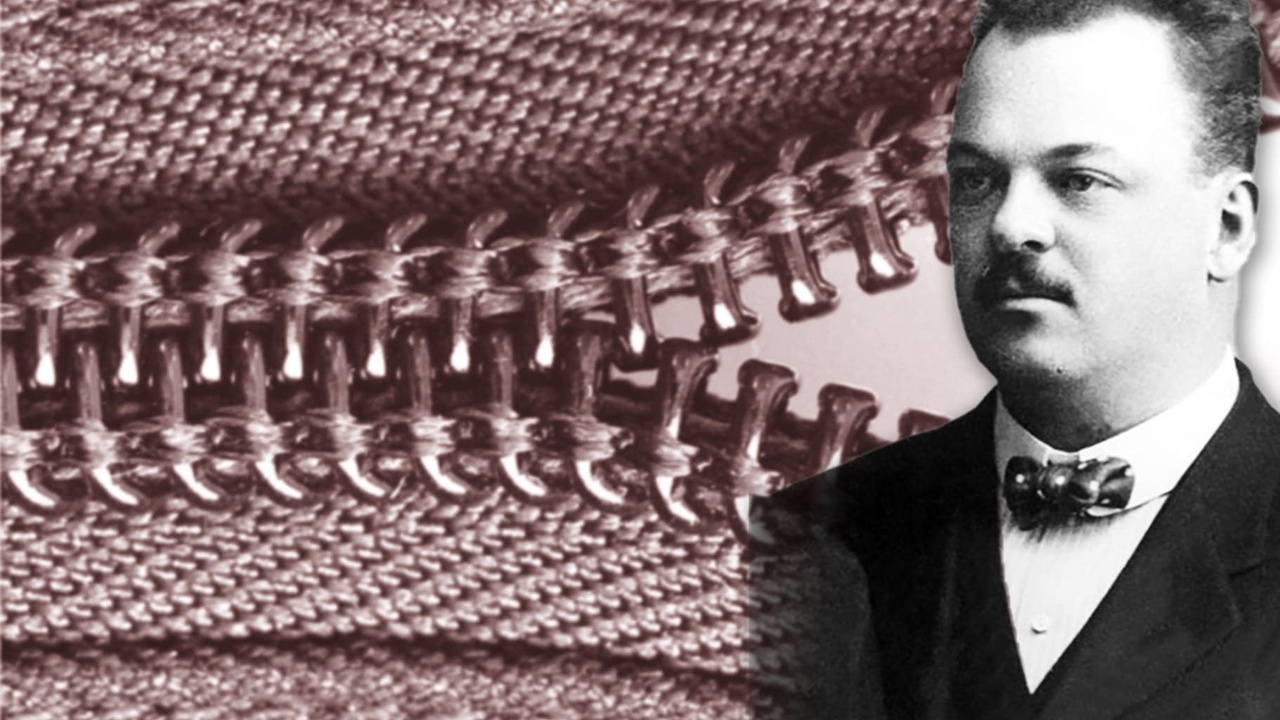

On This Day, March 20, 1917, the modern all-purpose zipper is patented, by Gideon Sundback.

These days, zippers are so commonplace on clothing that we don’t really them–until they stop working. We routinely take them for granted. We zip them up and down many times daily without ever giving a second thought to who invented them, how complex they are, or how much of an innovation they were more than a century ago.

But today, take a look at a zipper on whatever you’re wearing. You’ll see the little teeth are lined up on two separate pieces of cloth tape. The slider device that unites the teeth has to move smoothly up and down, or side-to-side, and it requires a small but easy-to-use pull-tab. Once closed, the teeth need to provide a firm hold. Zippers also need a “stop” piece at both the top and the bottom of the zipper to keep a slider from running off its track.

The challenge of the earliest zippers was making ones that were reliable and that would lie flat. If the zipper buckled, twisted, or gapped open, it wasn’t any good to anyone.

While Gideon Sundback is credited with inventing the first zipper, he wasn’t the first to patent a zipper-like device. Sundback, however, created the first zipper that worked well, and he also invented the machine that could make these fasteners more quickly and efficiently. So he’s commonly referred to as the inventor of the modern zipper.

The zipper was, in every way, an evolution of invention and evolution, and the innovation of several men responsible for that the evolution:

Elias Howe

The first known effort at making this type of closure system was made by Elias Howe, and in 1851 he received a patent for an "Automatic, Continuous Clothing Closure".

His invention was a series of clasps united by a connecting cord that slid up and down on ribs. It was called an “automatic continuous clothing closure,” but it was never marketed.

Howe, perhaps because of the success of his sewing machine, did not try to seriously market it, missing recognition he might otherwise have received.

Whitcomb Judson

Forty years later, Whitcomb Judson, a mechanical engineer, was tired of fastening the high-button boots that were in fashion at the time. He developed a hook-and-eye fastener that featured a hand-pulled guide to clasp hooks and eyes sequentially, thereby closing the boot or the article of clothing.

The debut of the zipper in the U. S Patent Office was made in 1893 by inventor W. L. Judson; however, the design was more promising than practical.

Judson spent two years drawing and re-drawing the closure he envisioned. At last he got a patent on what he called the “clasp locker.” The device was inventive enough that it was accepted for display at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Because of this exposure, Judson received investment money from Lewis Walker, and the two men started the Automatic Hook & Eye Company (later known as the Universal Fastener Company) in 1893.

The company moved from Chicago to Hoboken, New Jersey, and would later be renamed as “The Talon Zipper company” when it finally moved to Meadville, Pennsylvania. It became the first manufacturer of zippers.

While the idea was there, the marketing and practicality was not, and the zipper failed to catch on. The technology was still problematic. Sometimes the interlocking part of it didn’t mesh, and other times, the fastenings popped open. But Judson saw the need was real and kept at it.

Throughout the 19th century, all clothing, suitcases, pouches and shoes had to be fastened closed using buttons, snaps, buckles, or some sort of system of pins. These closures were not speedy or convenient.

The first of his zippers were not much of an improvement over simpler buttons, and innovations came slowly over the next decade.

Ultimately, Judson invented a zipper that would part completely (like the zippers found on today's jackets), and he discovered it was better to clamp the teeth directly onto a cloth tape that could be sewn into a garment, rather than have the teeth themselves sewn into the garment.

Zippers were still subject to popping open and sticking as late as 1906,

And with some items of clothing, the assistance of another person was required.

The Universal Fastener Company enjoyed some early sales, but business was slow. Judson knew the product still needed work. Gideon Sundback was hired to address the problem.

Gideon Sundback’s Story

Gideon Sundback was born in Sweden in 1880 and finished his electrical engineering studies in Germany before emigrating to the United States in 1905. His first job was at Westinghouse Electric Company. About a year later, he received an offer from Whitcomb Judson.

After ingratiating himself with the company through his good skills (and by marrying the plant manager’s daughter), Gideon Sundback was made head of design at Universal Fastener in 1906.

His first development is known as the Plako fastener. The Plako fastener operated with the closure guide carefully moving up the tracking loop through the hooks and eyes that were attached to cotton twill tape on either side.

It was considered a “bridge” technology as it was a stepping stone to what was eventually going to be the zipper. (The Plako patent–#788317–was filed under Whitcomb Judson’s name, but companies frequently kept patents in their founders’ names.)

Sundback continued to work on the design, and in 1913, he received a patent for what he called “the Hookless No. 2.” In 1917, he patented changes he made to the 1913 design. With the 1917 patent, Sundback improved many of the flaws that had bothered them all. He found a way to manufacture “cup-shaped teeth” that interlocked; each pair nesting within the pair below as the fastener was pulled between the two sides.

Sundback also invented a machine that could make the separate strips with teeth. The first factory was built in St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, just west of Niagara Falls. Sundback spent time traveling between the company’s main office in Meadville, Pennsylvania, and the plant in Canada to supervise the work.

His was just like the zipper of today, except for one major remaining flaw: it would rust after going through the wash. He saw a little more success in his early days than Judson did before him, but still no one really wanted them.

This could be in part because no one could seem to figure out just how to use it. It was so confusing to people at the time that the so called “separable fasteners” had to be sold with a set of instructions.

The design for the modern zip invented by Sundback was later to be called the “Talon Slide Fastener.”

It took another 20 years for the garment industry to adapt the zipper for use on jeans, jackets, and trousers.

In 1918, Zippers were first successfully used on tobacco pouches.

The U.S. military saw the promise of this new type of closure device—faster and easier than any type of button or snap. In 1918, the Navy ordered 10,000 hookless fasteners for their flight suits.

Other parts of the military experimented with them on life vests and money belts.

The army did buy a bunch of them to use on their clothing and equipment, but other than that, really nothing was selling.

He said that he liked the sound these ˜separable fasteners’ made (i.e. Z-z-zip) and from that, he coined the word ˜zipper’ and the name stuck.

But just as Whitcomb Judson knew when he began tinkering with creating the fastener; in 1922, a designer at B.F. Goodrich saw the possibilities. He realized that if rubber boots could be closed in this way, it would reduce the amount of water that seeped in—a problem they had with other types of closures.

A year later, B.F. Goodrich decided to order 150,000 of the new devices to use on his new product of the day—rubber galoshes.

The boots, which were originally going to be named the Mystik Boot, were renamed the Zipper when Goodrich employees reported that the company’s president showed boundless enthusiasm for the new design. The term zipper, initially the name of just the boot, eventually came to signify Sundback’s invention as well when a Goodrich executive in Akron, Ohio coined the phrase “Zip ‘er up,” also echoing the sound made by Sundback’s invention, and the name zipper was permanently attached to the actual fastening device.

The company registered Zipper as a trademark in 1925.

Goodrich had them added to a new style of boot they were making.

Soon after this success, the zipper was added to clothing of various types.

It was a hard sell in the early days for consumer clothing, with critics labeling the zipper a morally corrupt invention that made it too easy to remove one's pants.

After a slow start, zipper sales soared. By comparison: In 1917, 24,000 zippers were sold; in 1934, the number had risen to 60 million.

The Third Era of Zipper History

In 1935, Elsa Schiaparelli was one of the first couturiers to use zippers in garments. Over time, more garment makers did so. In the 1930s, Esquire magazine featured the “newest tailoring idea for men,” raving about the zippered fly. With new colors available, zippers became a must-have item on clothing of all types.

By 1934, 60 million zippers sold during a year. They were being used on men’s and women’s clothing, sleeping bags, handbags, and eventually knapsacks and suitcases.

Zippers really took off in 1937, when they caught the attention of a number of French fashion designers.

In a decade when most other companies were firing workers and struggling to survive, Talon’s Meadville factories had to go to twenty-four hour production to meet demand. At the height of the zipper’s popularity the Meadville zipper factories employed 5,000 workers — out of a town with fewer than 19,000 people.

Talon had its best year ever in 1941, when demand for the zipper earned the company thirty-one million dollars in sales. Months later, wartime shortages dried up the supplies of copper alloy that the Meadville factories needed for their machines. For Meadville, the boom was over. Talon’s Meadville operations never recovered.

War Shortages

In 1940, Research on coil zippers began in Europe. The early ones were made of brass which tended to bend. After the discovery of flexible synthetics, the polyester coil zipper was developed.

War shortages eventually led to making zippers out of plastic, and the industry adapted. But the zipper business still suffered because raw goods were still in short supply because of the war.

Gideon Sundback died of heart disease on June 21, 1954 at the age of 74 in Meadville, Pennsylvania.

That same year, Levi’s introduced a special zippered version of its overalls called the 501Z, replacing the button-fly. The company eventually brought in zippers across its line of jeans, but not until the 1970s.

Talon flourished through the 1960s when it is estimated that seven out of every 10 zippers were Talon zippers. ...But that would change.

Talon Zippers slipped rapidly as the largest producer of zippers—due largely due to the rise of a Japanese company called, YKK—a zipper manufacturer named after Tadao Yoshida, who founded it in 1934.

YKK

Initially, YKK zippers got off to a rough start. They were made by hand, and had an inferior quality compared to automated zippers from abroad. But in 1950, YKK purchased a chain machine from the U.S. that allowed the automation of the zipper making process. YKK's first US office opened in New York City in 1960.

Meanwhile, Talon had allowed its patents to run-out and offshore production of zippers soon overtook the company. In 1960, the conglomerate Textron bought the company and it turned out to be a disaster for Talon. Textron’s mismanagement lead to the purchase of the company by British firm Coats and Viyella in 1991.

Although the zipper market in the 1960s was dominated by Talon, and a German company, Optilon.

YKK surpassed them both in the American market and became the industry giant sometime in the 1980s, ultimately forcing Talon to mostly forgo the zipper business.

Zippers are big business. The global market for zippers is estimated at $8.2 billion in 2013 and is expected to hit $11.7 billion by 2018.

YKK was holds 46% of world market share in zipper sales, followed by KCC Zipper, Tex Corp., Optilon, Talon Zipper, and a large group of smaller Chinese manufacturers.

For YKK, that’s more than 7 billion zippers each year.

So today, when you take a close look at the zippers on your clothes, there’s a good chance you'll see the letters "YKK," in all capitals, on a lot of them. They're on everything from jeans, to coats, to sleeping bags.

Those letters stand for "Yoshida Kogyo Kabushikikaisha" which, from Japanese, roughly translates to "Yoshida Company Limited." In January 1946, the company registered the YKK trademark.

Today, the company has grown to 80 companies, 42,154 employees, in a total of 206 facilities around the world. They can be found in 72 different countries. In other words, YKK has the industry all zipped up: The company accounts for 46 percent of the global zipper market.

YKK’s success may be largely due to the fact that the company has brought all of its production in house. It smelts its own brass, concocts its own polyester, spins and twists its own thread, weaves and color-dyes cloth for its zipper tapes, forges and molds its scooped zipper teeth. YKK even makes the boxes it ships its zippers in. And of course, it still manufactures its own zipper-manufacturing machines—which it carefully hides from the eyes of competitors. With every tiny detail handled under YKK’s roof, outside variables get eliminated and the company can assure consistent quality and speed of production.

The company’s Chairman and CEO, Tadahiro Yoshida also preaches a management principle he calls “The Cycle of Goodness.” It holds that “no one prospers unless he renders benefit to others.” In practice, this boiled down to Yoshida striving to produce ever-higher quality with lower costs. YKK makes very dependable zippers, ships them on time, offers a wide range of colors, materials, and styles, and never gets badly undercut on price.

The prevailing feeling in the apparel industry is that you can’t go wrong with YKK—they’ve effectively established themselves as the “old reliable,” must-have zipper.

“There have been quality problems in the past when we’ve used cheaper zippers,” says Trina Turk, who designs her own line of women’s contemporary sportswear. “Now we just stick with YKK. When the customer is buying $200 pants, they better have a good zipper. Because the customer will blame the maker of the whole garment even if the zipper was the part that failed.”

A typical 14-inch “invisible” YKK nylon zipper (the kind that disappears behind fabric when you zip up the back of a dress) costs about 32 cents. For an apparel maker designing a garment that will cost $40-$65 to manufacture, and will retail for three times that much or more, it’s simply not worth it to skimp. “The last thing we want to do is go with a competitor to save eight or nine cents per zipper and then have those zippers pop,” said Turk. “The cost difference just isn’t enough given the overall margins.”

Today, by the way, Talon is back to being a major zipper manufacturer, and it's still used by brands like Brooks Brothers and Uniqlo.

Some Zipper Trivia:

1. There are 4.5 billion zippers of all kinds consumed in the U.S. per year. That’s 14 zippers for every American per year.

2. Every year, YKK produces enough zippers to wrap around the world 50 times. That’s 1.2 million miles of zippers! The national Manufacturing Center of YKK in Macon, Georgia produces around 65,000 miles of those zippers annually.

3. YKK makes airtight zippers for spacesuits, flame retardant zippers for fire suits, airtight zippers for bagpipes and zippers for fish farm nets. In fact, on July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong took “one giant leap for man kind” as the first man on the moon, guess what zipper kept his suit on? You guessed it – YKK.

4. In 2006, the National inventors Hall of Fame inducted Gideon Sundback into their ranks.

5. In 2012, Sundback and the zipper were further honored by becoming a Google doodle.

Today, chances are, the zip that keeps your valuables in place started life in a factory in the Qiaotou, a dusty town in Zhejiang Province, China. Qiaotou's zip plants manufacture 80% of the world's zips, churning out 124,000 miles of zip each year—enough to stretch five times round the globe or halfway to the moon.

Travel Tip: Today, you can dine at the summer home of Gideon Sundback —The Venango Valley Inn and Golf Course in Venango, PA, located between Cambridge Springs and Saegertown in Crawford County.

Tip for a stuck zipper: A Q-Tip dipped in shampoo and rubbed into the area where a zipper is caught on a jacket can get it unstuck.

Nostalgia Tip: Talon is still rightly celebrated by nostalgists and historical purists, as it’s a window to America’s manufacturing past. While vintage shopping, it wouldn’t be shocking to find a classic Talon zipper on a perfectly-aged Schott NYC leather jacket and you can still see them today on repro jeans from Levi’s Vintage Clothing, Lee 101, and Sugar Cane.

Zipper Quotes

"First you forget names, then you forget faces. Next you forget to pull your zipper up and finally, you forget to pull it down."

—George Burns

“My father was totally interested in quality; this was his hallmark. He didn’t quit when he had something partially done. Perfecting the zipper was what kept him going for a long time.”

—Eric Sundback, Gideon’s son.

So, the zipper has a long, fascinating history. The next time you zip up your pants or your dress, and you’re rushing out the door, closing up your clothes with ease, be sure to thank Gideon Sundback.

Because, no doubt, without him, you’d be 5 minutes late...