Washington Monument Dedicated

Feb 21, 2021

On this Day, February 21, 1885, dedication ceremonies are held for the first national monument to honor George Washington. Construction had begun in 1848, but was halted from 1854 to 1877 due to a lack of funds.

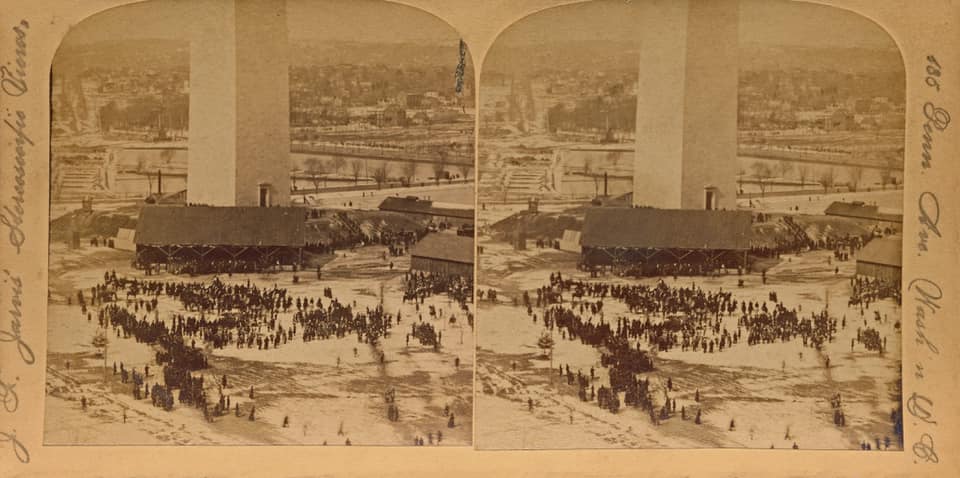

Despite being an exceptionally cold and windy day, the Dedication saw a footfall of more than 800 people, which took place on the monument grounds.

“First in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen.” President Chester Alan Arthur opened his dedicating speech with this line as he remembered the first American President and his service to his country.

As early as 1783, when Washington was very much alive, plans were in the works for erecting a large statue of the first president on horseback near the Capitol building. In fact, the architect of Washington, D.C., the French landscape engineer Charles Pierre L'Enfant, left an open place for the statue in his drawings. And that's almost exactly where the Washington Monument sits today.

Congress failed to act on the equestrian statue, and even after Washington died in 1799, legislators couldn't agree on what kind of monument best suited the national hero. Frustrated with congressional feet-dragging, a private organization called the Washington National Monument Society was formed in 1833 to raise money and solicit designs for a large-scale homage to America's beloved first president.

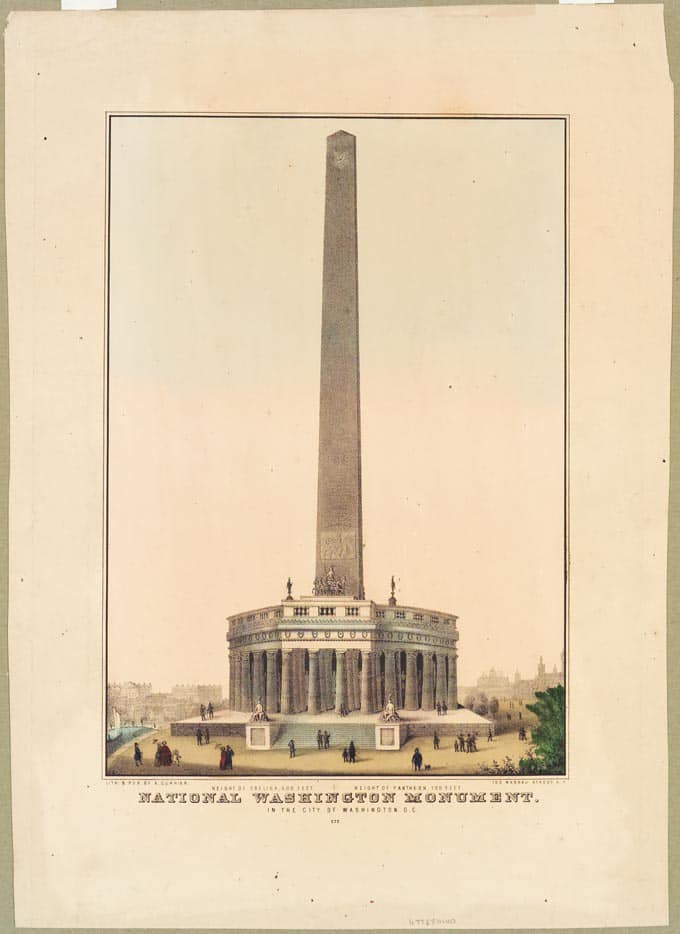

In 1836, the Washington National Monument Society announced a design contest for the future Washington Monument and the winning sketch was submitted by 29-year-old architect Robert Mills, who would go on to design the U.S. Post Office, the Patent Office and the Treasury Building.

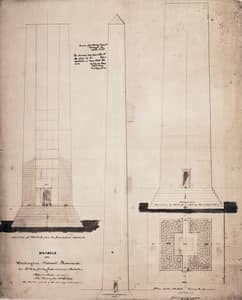

Mills' original design was a mashup of architectural references. First, there was to be a 600-foot (182-meter) obelisk with a flattened top, a nod to the Egyptomania that had captured the early 19th-century imagination. (Soon after Washington's death, the House of Representatives proposed the construction of a marble pyramid, 100 feet on each side, to serve as the first president's mausoleum. The pharaohs would have approved, but Congress didn't.)

In Mills' original sketch, the giant Egyptian obelisk was to be encircled at its base by a neoclassical temple with 30 towering columns. On top of the circular temple would be a statue of Washington on a chariot, and in between each of the 30 columns would stand statues of 30 different revolutionary war heroes.

The National Park Service calls Mills' original plan "audacious, ambitious and expensive," which explains why all but the obelisk was eventually scrapped.

An estimated 15,000 to 20,000 crowded the National Mall to witness the laying of the Washington Monument's cornerstone on July 4, 1848. But first the 24,500-pound hunk of pure white marble had to be dragged through the streets on a cart with bystanders grabbing lengths of rope to help the cause.

By 1856, after eight years of slow and painstaking construction, the obelisk stood 156 feet (47 meters) high and would remain that way — an unfinished eyesore that Mark Twain called "a hollow, oversized chimney" — for the next 21 years. The reason, strangely enough, had to do with the Pope.

In 1853, the Washington National Monument Society was dangerously low on funds, so they came up with a scheme whereby large donors could have a commemorative stone placed in the interior of the obelisk. One of those donors ended up being Pope Pius IX, who shipped over a 3-foot (91-centimeter) piece of marble from the Temple of Concord in Rome.

The Pope's gift upset members of the new "Know-Nothing" party, who were virulently anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic. On the night of March 6, 1854, a gang of men locked the night watchman in his shed and stole the Pope's stone, allegedly tossing it in the Potomac.

The controversy over the stolen stone brought donations to a standstill. But even worse was what happened next; a contingent of Know-Nothings staged a coup and overthrew the leadership of the Monument Society. Donations dried up entirely and the Know-Nothings only managed to add 20 more feet (6 meters) to the obelisk by the outbreak of the Civil War, when construction was halted altogether.

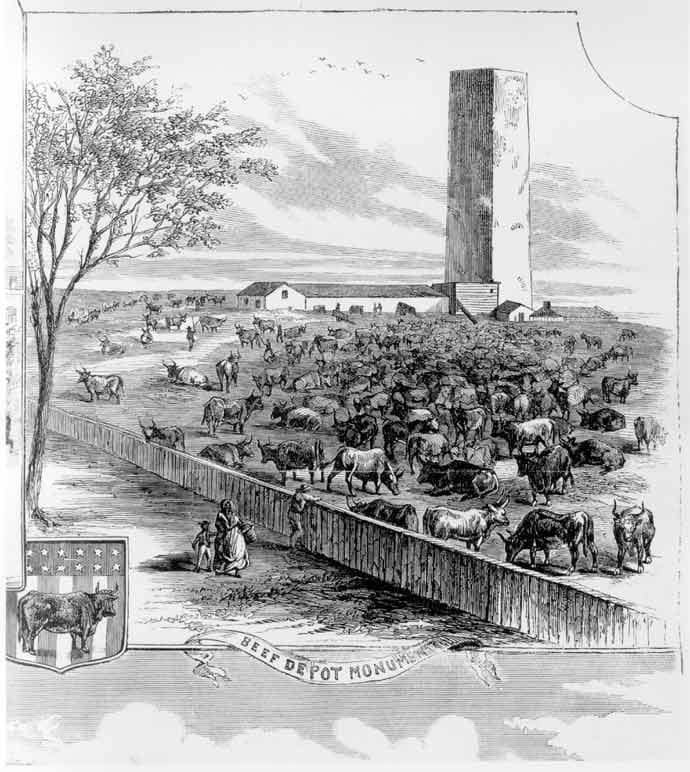

After the Civil War, during which the grounds of the stubby Washington Monument were used as a cattle yard and slaughterhouse, Congress finally decided to take over. On July 5, 1876, in time for the centennial celebration of the Declaration of Independence, Congress appropriated $2 million for the completion of the monument and construction resumed in 1877.

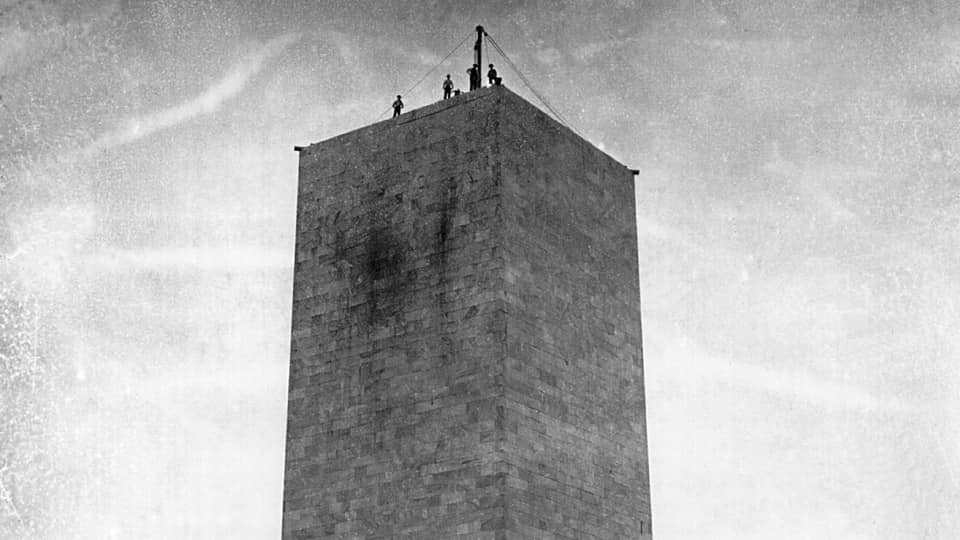

The first task of the new chief engineer, Thomas L. Casey, was to reduce the total height of the obelisk to 555 feet (169 meters), exactly 10 times the width of the structure, and to spend years reinforcing the foundation with concrete.

The next issue was the masonry. The original quarry in Baltimore had shut down, so Casey tried shipping down rock from Massachusetts. But after placing only a few layers of this stone, it was clear that it was a different color and of poorer quality than the original. So, the builders changed tack yet again and brought in stone from another Baltimore quarry, which was used to finish the final two-thirds of the obelisk.

The result is that the Washington Monument is nearly white on the bottom, a tannish-pink on the top with a thin belt of light brown in the middle.

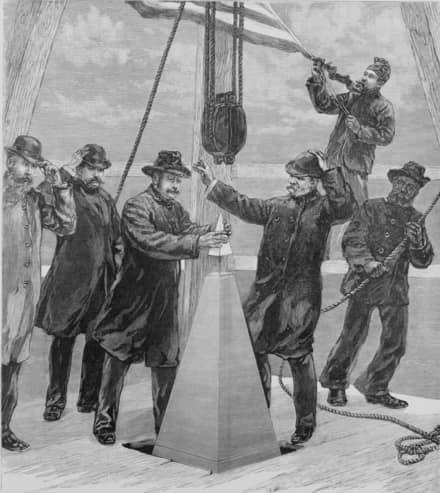

Construction of the obelisk was finally completed on Dec. 6, 1884, more than 36 years after the first cornerstone was laid, with the ceremonial setting of the capstone.

The final cost of the Washington Monument was $1.18 million in 1884 or nearly $30 million in today’s dollars.

For five years, It was the world's tallest manmade structure. And then Eiffel built his tower in 1789, which at 1,063 feet (324 meters) is nearly twice as tall as the Washington Monument.

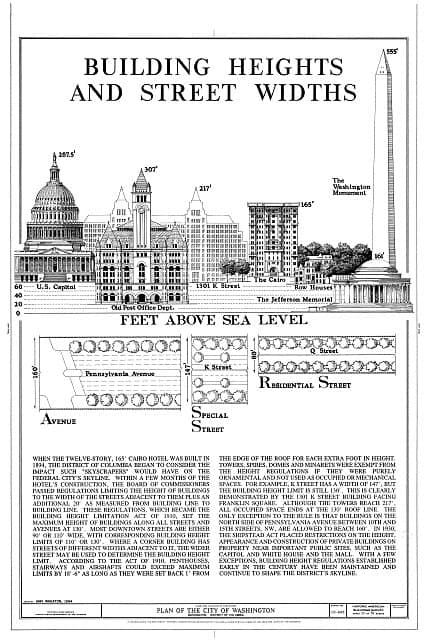

But the Washington Monument is — and probably always will be — the tallest structure by far in Washington, D.C., although not for the reasons you might have heard. It has nothing to do with city planners who didn't want any building to block the view of the Capitol Building or the Washington Monument.

The height limits on buildings in the District of Columbia were established by the Height of Buildings Acts of 1899 and 1910, which were primarily concerned with the fire safety of new construction methods that allowed buildings to be raised to incredible new heights. The laws, which are still on the books in D.C., restrict the height of buildings to the width of the street in front of them, which is 130 feet (40 meters) in most places and 160 feet (49 meters) on Pennsylvania Avenue.

Other dignitaries who delivered a speech at this event were Ohio Senator John Sherman, the Rev. Henderson Suter and Freemason Myron M. Parker. William Wilson Corcoran, of the Washington National Monument Society, was absent and his speech was read by Dr. James C. Welling.

It was succeeded by a brief Masonic ceremony and a speech by the Engineer of the Monument, Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey of the Army Corps of Engineers.

Following the speeches, Lieutenant-General Philip Sheridan led a procession, which included the dignitaries and the crowd, past the Executive Mansion, then via Pennsylvania Avenue to the east main entrance of the Capitol, where President Arthur received passing troops.

Then, in the Executive Mansion the President, his Cabinet, diplomats and others listened to Representative John Davis Long read a speech written a few months earlier by Robert C. Winthrop, who was the Speaker of the House of Representatives when the cornerstone was laid 37 years earlier. He couldn’t make it because of his illness.

Because George Washington was born in the state of Virginia, the final speech was given by John W. Daniel, governor of Virginia. The festivities concluded with fireworks, both aerial and ground displays.