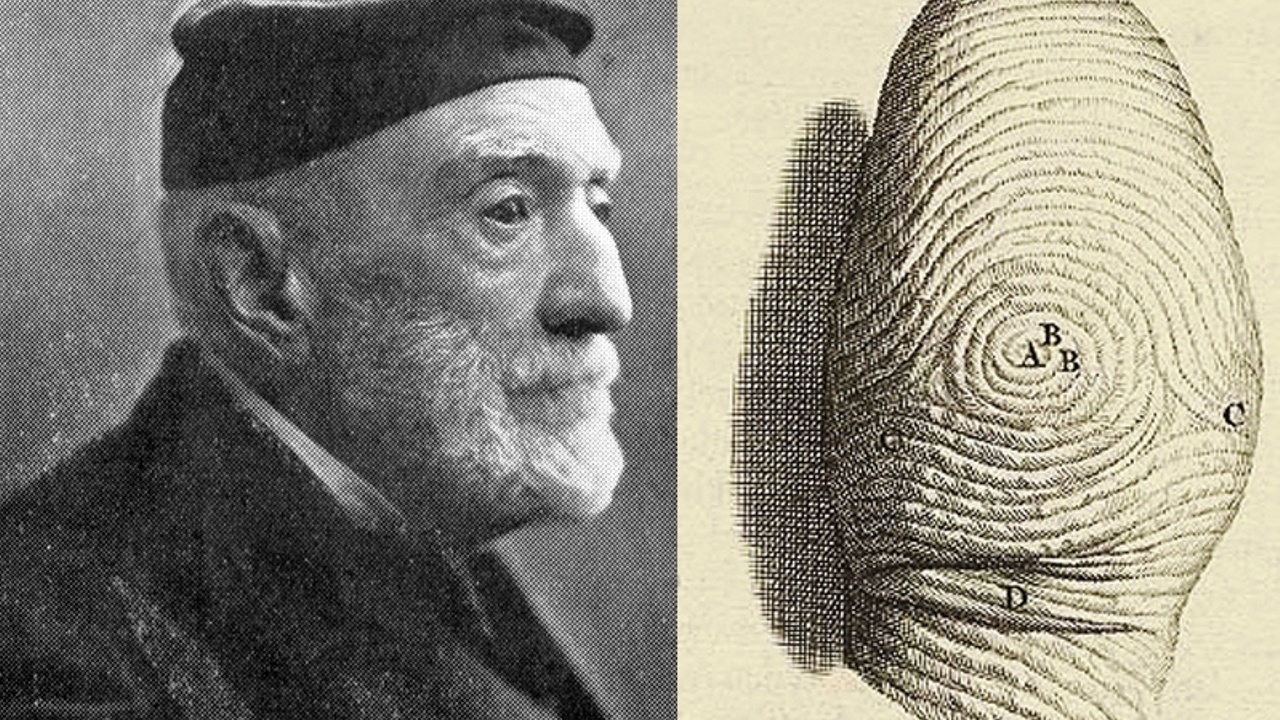

Henry Faulds was a Scottish doctor, missionary and scientist who has become widely known as the "Father of Fingerprinting." In 1880, he was the first to suggest using fingerprints for criminal investigations using a classification system that he developed. But during his lifetime, he never received the credit for his discovery. Here is his story...

Henry Faulds was born on June 1, 1843 in Beith, Scotland. His parents were initially wealthy but lost much of their fortunes following the City of Glasgow bank collapse in 1855.

Unable to continue his education, Henry had to drop out of school as a 13 year old to take up a job and to help support his family. He found employment as a clerk. Later on he became apprenticed to a shawl manufacturer. After working for a few years he decided to further his education. He was a bright young man and at the age of 21 he started attending classes in mathematics, logic, and classics at Glasgow University.

However, it was not long before he realized that his true passion was to study medicine. When he was 25, he enrolled at Anderson's College from where he received his physician's license.

During his college years he also developed a strong faith in Christianity and was attracted towards missionary work.

Following graduation, Faulds then became a medical missionary for the Church of Scotland. In 1871, he was sent to British India, where he worked for two years in Darjeeling at a hospital for the poor.

On 23 July 1873, he received a letter of appointment from the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland to establish a medical mission in Japan. He married Isabella Wilson that September, and the newlyweds departed for Japan in December.

Accompanied by his new wife, he travelled to Japan the same year in order to establish a medical mission. Upon reaching Japan he established the first Scottish mission with the Tsukiji hospital and a teaching facility for Japanese medical students. He proved to be a very capable physician and soon gained respect among the locals.

He was influential in the founding of the Rakuzenkai, Japan's first society for the blind, in 1875 and a school for the blind in 1880. He also set up lifeguard stations in nearby canals to prevent drowning.

Faulds continued to contribute in a full variety of ways. He established the first English speaking mission in Japan in 1874, with a hospital and a teaching facility for Japanese medical students. He helped introduce Joseph Lister's antiseptic methods to Japanese surgeons. In 1875, he helped found Japan's first society for the blind, and set up lifeguard stations to prevent drowning in nearby canals. He halted a rabies epidemic that killed small children who played with infected mice, and he helped stop the spread of cholera in Japan. He even cured a plague infecting the local fishmonger's stock of carp. In 1880 he helped found a school for the blind. By 1882, his Tsukiji Hospital in Tokyo treated 15,000 patients annually. Faulds became fluent in Japanese, and in addition to his full-time work as a doctor, he wrote two books on travel in the Far East, many academic articles, and started three magazines.

But it was a simple expedition with his friend, American archaeologist, Edward S. Morse, to an archaeological dig, that was to be the turning point of Faulds’ career. On that dig, Faulds became intrigued by the impressions—lines and swirls—left by craftsmen on ancient the cooking pots made of clay. Could these patterns of ridges be unique to each individual, Faulds wondered?

A few months earlier he had been lecturing his students on touch and had noticed the swirling ridges on his own fingertips. He made the connection and realized that the impressions on the clay vessels came from the ridges on the fingers of ancient potters.

He was now intrigued with the idea of studying fingerprints and over the next few years undertook a series of experiments in order to examine fingerprints with a scientific approach.

He along with his medical students shaved off the ridges on their fingers and later observed that the ridges grew back in exactly the same patterns.

He also studied the fingerprints of infants and children to check if growth affected their fingertip patterns. When an epidemic of scarlet fever swept through Japan, causing severe peeling of the skin, Faulds found no before-and-after change.

After conducting several experiments and examining a significant collection of fingerprints, Henry Faulds came to the conclusion that each person has a unique fingerprint.

In 1850, attempting to promote the idea of fingerprint identification, Faulds sought the help of the noted naturalist Charles Darwin. Darwin, in advanced age and ill health, informed Faulds that he could be of no assistance to him but promised to pass the materials on to his cousin, Francis Galton, who forwarded it to the Anthropological Society of London. When Galton returned to the topic some eight years later, he paid little attention to Faulds' letter.

His theory was soon put to the test. Shortly after the expedition, Faulds’ Tokyo hospital was broken into, and to his dismay a trusted colleague was suspected of the crime. Convinced of the man’s innocence, and determined to exonerate the man, he compared the fingerprints left behind at the crime scene to those of the suspect and found them to be different. On the strength of this evidence the police agreed to release the suspect.

A thief climbed a wall near his house and left sooty fingerprints on its whitewashed surface. When the police arrested a suspect, Faulds asked them if he could take fingerprints from their prisoner. He found that the fingerprints he took from the suspect did not match those on the wall and advised the police that they had detained the wrong man. Another suspect was taken into custody. This time the suspect's prints matched, and he confessed to the crime. This was the first recorded occasion when both innocence and guilt were proven by the use of fingerprints. This incident is what gave Faulds the confidence and perseverance to continue with his beliefs and studies.

While still in Japan, triumphant at his discovery, Faulds wrote to Nature journal. On October 28, 1880, Faulds' first paper on the subject, entitled "On the Skin-Furrows of the Hand," was published in the scientific journal.

In that paper he made two important observations: "(1) When bloody finger-marks or impressions on clay, glass etc., exist, they may lead to the scientific identification of criminals, and (2) A common slate or smooth board of any kind, or a sheet of tin, spread over very thinly and evenly with printer's ink, is all that is required [to take fingerprints]." This was the first recorded suggestion that fingerprints could be used to locate criminals, and how it might be done.

Faulds not only recognized the importance of fingerprints as a means of identification, but he devised a method of classification as well. Additionally, through his experiments Faulds was the first to discover that fingerprints do not change throughout one's life.

Faulk’s paper included a remarkable forecast that fingerprints from mutilated or dismembered corpses might be of forensic importance in identification.

Furthermore, Faulds anticipated the transmission of fingerprints by photo-telegraphy. He also suggested that criminal registers be kept of "the for-ever-unchangeable finger-furrows of important criminals."

Shortly after the publication of this paper, Sir William Herschel, a British civil servant based in India, wrote to ‘Nature’ claiming that he had been using fingerprints as a means to identify criminals in jail since 1857. This created considerable controversy and resulted in bitter feuds between the two men. Later on, Herschel himself gave full credit to Faulds for his original discovery.

Some controversy has arisen about the inventor of modern forensic fingerprinting. However, there can be no doubt that Faulds' first paper on the subject was published in the scientific journal Nature in 1880; all parties conceded this.

Later, Herschel published another letter in Nature, giving full credit to Faulds for his original discovery. This disclaimer went largely unnoticed and others had by this time usurped Faulds' place in history.

After a quarrel with the missionary society which ran his hospital in Japan, and due to his wife's illness, Faulds returned to Britain in 1886, and offered his fingerprinting system to Scotland Yard, and the major police forces around the world.

But Scotland Yard dismissed the offer probably because Faulds did not present the extensive evidence that proved that fingerprints are unique, durable, and practically classifiable. They later regretted the decision.

In 1892, Francis Galton published a book on the use of fingerprints, with no mention made of Faulds' contribution.

In 1901 Edward Henry, a former colleague of Galton and the Commissioner of Police at Scotland Yard, finally set up a fingerprint bureau.

Galton, Herschel, and Henry are the three me to whom credit is frequently given for the discovery of the use of fingerprints in criminology.

The Japanese police officially adopted the fingerprinting system in 1911.

His clinic in Tokyo was bought by Ludolph Teusler and became St. Luke's International Hospital.

Understandably perhaps, Faulds became embittered. He returned to the life of a police surgeon, at first in London, and then in the Stoke-on-Trent town of Fenton.

In 1922 he sold his practice and moved to James Street in nearby Wolstanton, where he died on this day, March 19, 1930 at the age of 86, in obscurity, and bitter at the lack of recognition he had received for his work.

It took well over 50 years for Faulds to receive the credit he deserved as the Father of Forensic Fingerprinting.

In 2007 a plaque acknowledging Faulds' work was unveiled at Bank House, near to Wolstanton's St Margaret's churchyard where his grave can be seen.

In 2011, a plaque was unveiled at his former James Street residence.

On 12 November 2004 a memorial was dedicated to his memory in Beith town centre close to the site of the house in New Street where he was born.

In 1920s USA, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover ordered the compilation of a national pool of fingerprints, which quickly grew to a database of more than 5 million records.

But with no reliable way to index fingerprints, finding matches could take months. It wasn't until the 1970s and the emergence of the early computer-based systems that the response time became quick enough to prove helpful.

Nonetheless, today it’s safe to say we have Henry Faulds to thank for the science of Forensic Fingerprinting.

#OTD #History #Fingerprinting #Fingerprints #Forensics #Leaders #Innovation#Innovators #Crime