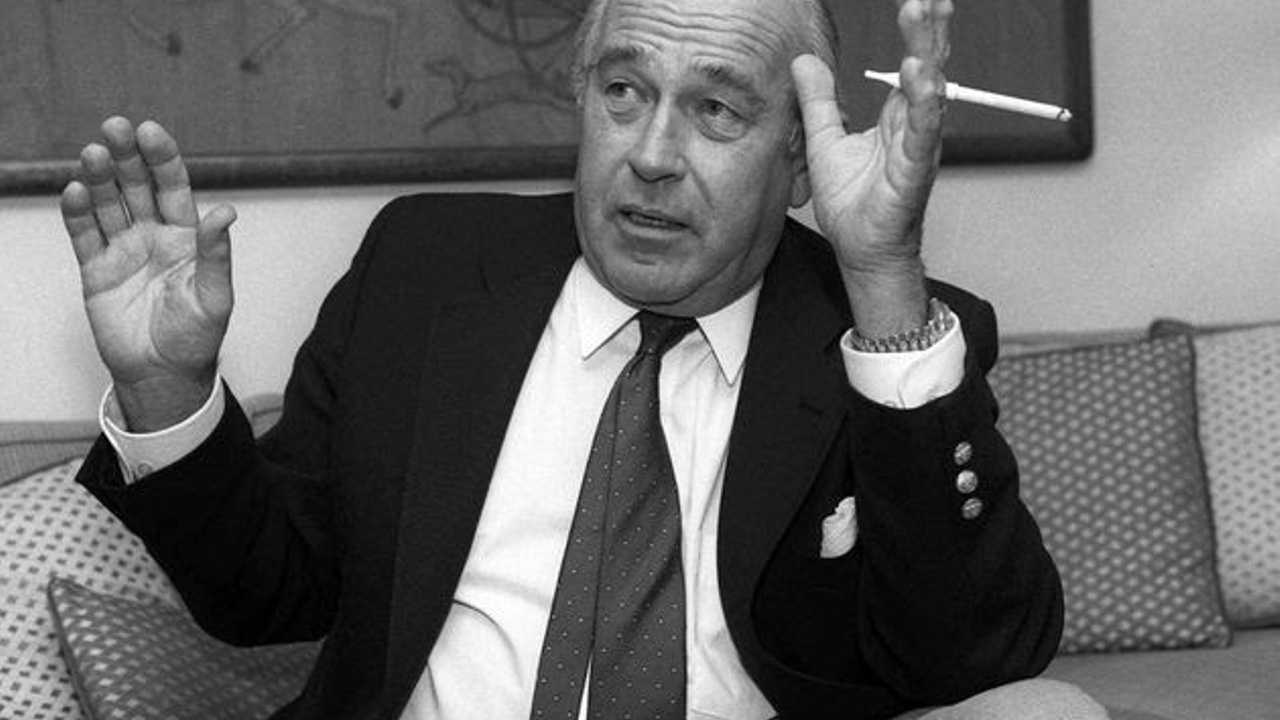

Robert Ludlum—Famed Author of the Jason Bourne Thrillers: How His Life--and Death--Imitated his Art

Famed thriller author, Robert Ludlum died on this day, March 12, 2001. From The Scarlatti Inheritance and The Osterman Weekend, to the Bourne Supremacy, movies, digital games, and 41 other novels in-between, Ludlum will always be a hard act for any author to follow. The number of copies of Ludlum’s books in print is estimated up to 500 million: and his books have been published in 33 languages and 40 countries.

Perhaps less known, is that his life—as well as his death may parallel that of his most famous protagonist, Jason Bourne.

Robert Ludlum led a fascinating life.

Ludlum was born in New York City, the adopted son of Margaret Wadsworth and George Hartford Ludlum. He never found who his birth parents were.

As an adopted child, Robert Ludlum explored the limits of reasonable behavior and parental tolerance. After a seemingly endless period of rowdy behavior, this future superstar settled down at the famed Connecticut prep-school, Cheshire Academy, and began to establish himself as a credible student of the arts as well as exceptional athlete.

He then attended Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, where he earned a B.A. in Drama in 1951.

He entered the Marines after graduation and saw combat in the South Pacific. During his service, he penned a 100-page manuscript inspired by his time serving in the South Pacific.

Returning from war, he attended Wesleyan College in Connecticut, where he focused on theater and met his future wife. They got married, worked in television and theater together and opened a successful playhouse in northern New Jersey.

Ludlum’s first artistic love was the theater, where he worked as both an actor and producer. In the early 1950s, he made more than 200 TV appearances, mostly in live theatrical productions playing mostly criminals or lawyers. During the 1960s, he produced more than 300 plays for New York and regional theatres.

His theatrical experience may have contributed to his understanding of the energy, escapism and action that the public wanted in a novel. He once remarked: "I equate suspense and good theater in a very similar way. I think it's all suspense and what-happens-next. From that point of view, yes, I guess, I am theatrical."

Then one day, he saw two old black-and-white photographs juxtaposed side-by-side in a magazine: one of Nazi Party members parading in their uniforms, and the other of a wheelbarrow-load of hyper-inflated German Reichsmarks. And that triggered an idea – what if Adolf Hitler’s rise had been inspired by a shadowy group of international financiers? The result was a short story,

In 1971, at age 44, he decided to try to expand and transform that short story into a novel.

He’d long been a closet writer, and decided to send out that first full-length effort, titled, “The Scarlatti Inheritance,” and see what happened. His wife, Mary, encouraged him. “If you don’t do it now, you will regret it for the rest of your life,” she said to him.

It received many early rejections, but ultimately when The Scarlatti Inheritance was finally released, it was an instant hit as it landed on the shelves. Others soon followed.

His second book, The Osterman Weekend, was made into a film, as would The Holcroft Covenant and others.

The book’s success pushed Ludlum into becoming a full-time writer, following up on his early success with The Osterman Weekend and The Matlock Paper, and developing a trademark style that blended carefully researched fact and fiction into a compelling formula, perfect for the best-seller lists.

Though critics often found his plots unlikely and his prose uninspired, his fast-paced combination of international espionage, conspiracy, and mayhem proved enormously popular.

As a critic famously wrote of one of his books, “It was a lousy novel, so I stayed up until 3 a.m. to finish it.”

But Ludlum was unaffected by reviews and critics. Comparing his reviews to those of Charles Dickens, he once said, “The quality of an author’s work is not usually determined until after his death.”

During the 1970s, Ludlum lived in Leonia, New Jersey, where he spent hours each day with his wife, Mary, writing at his home.

Ludlum specialized in thrillers built on a foundation of paranoia and conspiracy theories, both historical and contemporary. His novels typically feature one heroic man, or a small group of crusading individuals, in a struggle against powerful adversaries whose intentions and motivations are evil and who are capable of using political and economic mechanisms in frightening ways. The world in his writings is one where global corporations, shadowy military forces and government organizations all conspired to preserve (if it was evil) or undermine (if it was law-abiding) the status quo.

For Robert Ludlum, life was indeed his mentor and model.

After publishing his first book, the world suddenly, inexplicably went dark for him. He was not able to remember anything for twelve hours. It was as though he no longer existed. No name. No memory. No past.

Ludlum’s affliction with temporary amnesia formed the backdrop for his most successful thrillers in print and on the screen: The Bourne Trilogy. He knew exactly what and how Jason Bourne must be feeling. Robert Ludlum had lived in the dark shadows before.

Richard Marek, famed editor at Scribner’s in Manhattan—received Ludlum’s manuscript for The Bourne Identity and reluctantly accepted it for publication based on his past successes.

Because Richard Marek was also the editor for my novel, The Sterling Forest, Marek related to me the extraordinary effort that he and his team were forced to go through in editing what he described as a “real mess of a manuscript, riddled with far too many grammatical and stylistic errors.” Over time, through a deep revision process, the errors were resolved, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Over a period of 30 years, he went on to average nearly one novel a year. And in the process he became enormously wealthy, with an income estimated at $5 million a year and a lifestyle that included a beachfront mansion in Florida, a ranch in Montana and a private jet. A significant part of that wealth had come from his three Jason Bourne books— among the biggest of his bestsellers.

But then, Mary, Ludlum’s wife and long-time soul-mate, died of cancer in 1996.

Lonely and depressed, he remarried within a few short months, and his friends were concerned. His new wife, Karen, was seen by Ludlum’s associates— many of them, former law enforcement and intelligence professionals—as being manipulative and self-interested.

Their concern mounted when soon, she began to isolate him from his friends and family. Even more ominously, when Ludlum’s lawyer proposed that she sign a pre-nuptial agreement, she refused, and threatened to end the relationship.

Ludlum went ahead and married her without the pre-nup.

Four years later, on March 12, 2001, he died of a heart attack, at his home in Naples, Florida, while recovering from severe burns sustained in a house fire the month prior.

A large part of his fortune went to Karen.

Nobody thought much of it at the time, but this is where Ludlum’s death closely resembles the stuff of his own novels.

It was only when his nephew, Doctor Kenneth Kearns began to collect material for Ludlum’s biography a few years later, that a different, more troublesome picture began to take shape.

Kearns later recounted, “Shortly after [Mary’s] untimely death, Uncle Robert remarried and his life turned bad. At first, I did not pay much attention to this aspect of his life.”

Through his continuing biographical research, however, a string of disconcerting facts surrounding his uncle’s death became more and more apparent.

Kearns put together a team of top lawyers and private investigators, and his research began to take on the nature of a criminal investigation.

Unsettling occurrences were uncovered. Like the fact that Ludlum had told one of his associates that a few days before the fire at his home, there’d been a probable attempt on his life on a lake near his Montana ranch.

Kearns went on to say, “Before hiring these professionals, I had found that key witnesses to Robert Ludlum's untimely death and a prior attempt on his life, would not talk. The pros took care of this problem. Six former FBI Agents conducted interviews in multiple states over a five month period, and the plot thickened. Robert's younger son Jonathan, who was in the process of investigating his father's death as well as beginning a challenge to the Ludlum Estate, disappeared two years ago and was ultimately found dead in his home. No one had heard from him for over a month. Karen Ludlum, Robert's second wife and the only witness to the event that took his life, died last year. The cause of death was listed as "suicide."”

There was money, greed, sex, power and unexplained death. Throughout the course of the investigation, every person in Robert Ludlum's life would be scrutinized.

The obvious next step would be to get the police to interrogate Karen Ludlum, and try to get at the truth. Except there was a problem: Karen Ludlum herself was, by now, dead.

Through that effort, Kearns discovered that in January 2001, Ludlum had changed his will, bequeathing the major portion to Karen, his new wife – and adding a codicil that anyone contesting the will would be cut out of it.

Two weeks later, on February 10, 2001, there was a mysterious fire in his home. When the fire service arrived, they found Ludlum trapped in his reclining chair and badly burned.

The only other person in the house was Karen. She was unscathed and uncooperative with authorities.

There were fire extinguishers in the house but none of them had been used. When the fire-fighters tried to question Karen she became aggressive and abusive, telling them to “Get the f*** out of here, I’m fixing myself a drink.”

Ludlum was in the hospital for weeks, being treated for burns (during which time Karen never visited him).

A month after he was discharged he died, ostensibly of a heart attack. There was no autopsy. And his body was hurriedly cremated. The cause of the fire was never found.

Shortly after, Karen was overheard by the domestic help having a long phone conversation with her lawyer about the will, and the amount that was due to her.

Officially, the records say that Robert Ludlum died of a heart attack.

Coincidence? Perhaps. But at what point do a string of coincidences become a trend? In this case, there are certainly many of them.

Thirteen Ludlum books have been released since Robert Ludlum’s death. The business is deployed now as a kind of film studio, presenting books completed by others or new ones written using his name.

“This goes back to 1990 or ’91 when Bob had quadruple bypass,” said Henry Morrison, Robert Ludlum’s agent. “One day we were talking about what would happen when he was gone. He said, ‘I don’t want my name to disappear. I’ve spent 30 years writing books and building an audience.’ ”

Many of Ludlum's novels have been made into films and mini-series. Although the story lines depart significantly from the actual books, The Bourne Ultimatum won three Academy Awards in 2008.

Close readers of Ludlum’s novels find serious themes running through each of them: the role of the individual in preserving democracy, the value of competing voices, the failure of educational institutions to preserve ideals, the temptations of power, the importance of personal loyalties in the face of impersonal organizations, and the nature of evil. Ludlum's novels are valuable in helping us to understand modern paranoia—our fear of conspiracies, terrorism, barbarism, and intolerance.

He would say, “Life is extremely complicated. I try as best I can to enter the realm of nuances of human behavior.”

When New York Times book critic John Leonard reviewed one of his thrillers, he wrote: “I sprained my wrist turning his pages.” Ludlum was a genius at creating narrative velocity. His books were jump started on the first page, then gradually picked up speed until it was difficult or the reader to pause long enough to take a breath. He was recognized as the king of high-speech techno thrillers.

In Ludlum’s case, since his death in 2001, his net worth has only increased. Eighteen books with his name on the covers have been published posthumously – largely books written by others in franchises he created – nearly equaling the number released during his lifetime. The Bourne franchise has been a huge success, with three films and five new books released since 2001 (not to mention videogame tie-ins). Often appearing in Forbes’ list of top-earning dead celebrities, Ludlum amassed an estate some estimate could now be worth $1 billion.

Ludlum once said, “It’s the hardest thing in the world to write the second book. The first one was easy. We’ve all got a story to tell. But writing the second book, that’s the difference between a professional and not a professional.”

In an interview, Ludlum was asked a series of questions.

Where did he find his ideas?

I love to observe people. I have always been interested in people who have decided to leave one lifestyle for another. On St. Thomas, I met a man named John who used to be a very successful ad man in New York. He threw it all away to follow a new dream – running a charter boat in the Caribbean. He went to a patrol school run by the Coast Guard in St. Thomas. He supported himself by becoming a disk jockey on a local radio station for $100 a week. Now he has his own charter boat business and is considered one of the more effective people on the island. A complete life change. Later I used that fact in The Bourne Identity. When one of my characters wanted to get away, he joined the boat people in the Caribbean.

What makes your locations so authentic?

My wife and I love to travel the world. And whenever possible, we take our kids and their wives with us. On a trip to Greece, they helped me gather restaurant menus, theater programs, ticket stub, tour brochures. And I take a lot of really bad pictures. But I put all this in a big scrapbook. The scrapbook brings memories back to life and helps make my writing more credible.

What is the biggest mistake made by beginning writers?

I get annoyed when a self-indulgent writer just shows off when he knows he doesn’t really tell a story. To me, storytelling is a craft. Then if you’re lucky, it becomes an art form. But first, it’s got to be a craft. You’ve got to have a beginning, middle, and end. And I have sort of applied the theatrical principles to writing. Throw the story in the air and see what’s going to happen.

In describing Robert Ludlum, he probably did it best. “I’m just a storyteller,” he once said. “I take my work seriously, but I don’t take myself seriously.”