The Two Men who Started California’s Gold Rush...But Never Profited From It

On this Day, February 28, 1849, the first prospectors for the Gold Rush of '49 arrive in San Francisco. Gold was discovered by James Marshall on Sutter's Mill the previous year. Over 300,000 people, known as "forty-niners" (from year 1849), would go to California to seek their fortune.

James Wilson Marshall was born to Philip Marshall and Sarah Wilson on his family’s homestead in Hopewell Township, New Jersey on October 8, 1810. The family homestead was known as the Round Mountain Farm and is still known as Marshalls Corner. He was the oldest of four children, and the only son. He followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a skilled carpenter and wheelwright.

At age eighteen, after his father died, James Marshall left New Jersey in 1834 and headed west. After spending time in Indiana and Illinois, he settled in Missouri in 1844, and began farming along the Missouri River near Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. There, he contracted malaria, and in 1844, on the advice of his doctor, Marshall to join a wagon train headed to California. in the hopes of improving his health. He joined an emigrant train heading west and arrived in Oregon's Willamette Valley in the spring of 1845.

In 1841, “Captain” John Sutter, an emigrant from (present-day) Germany received a grant of 48,000 acres along the Sacramento River. He was one of the very first ranchos in the great Central Valley of California. On a small rise a few miles back from the river he began building a new adobe fort, soon to be known as “Sutter’s Fort.”

As his empire expanded, he began to run out of building materials and looked eastward into the foothills for a source of suitable lumber.

After coming west on the Oregon Trail, Marshall had found Oregon too rainy and in June 1845 and headed south along the Siskiyou Trail into California, eventually coming upon Sutter’s Fort in mid-July and was immediately hired by the Captain to assist with work at the sawmill, and around the fort

California was still a Mexican possession in 1845.

Marshall was a man handy with tools, and he quickly made himself very useful with his wood and ironworking skills.

Sutter also helped Marshall to buy two leagues of land on the north side of Butte Creek and provided him with cattle. It was here that Marshall began his second stint as a farmer and rancher.

Soon after, in May 1846, the Mexican–American War began.

He was also among the up-and-coming settlers who joined forces with John C. Fremont early in 1846 to stage the Bear Flag Revolt, a premature bid to seize control of California that was snuffed out when American troops arrived to occupy the territory.

When he returned to his ranch in early 1847, he found that all his cattle had either strayed or been stolen. With his sole source of income gone, Marshall lost his land.

Soon, Marshall entered into a partnership with Sutter for the construction of a sawmill. Marshall was to oversee the construction and operation of the mill, and would share equally in the lumber produced. After searching the foothills for a suitable site, they selected a small valley on the South Fork of the American River, called by the Nisenan people “Cullumah.” This place had tall straight pine trees easily milled into lumber and a river for water power.

He proposed his plan to Sutter, and construction began in late August. By January the mill was half done. The crew then dug a ditch to carry river water through the sawmill. This ditch is called a millrace. They found that the tailrace—the lower end of the ditch—was much too shallow, so they spent several weeks deepening the tailrace so the water could flow through the mill without stopping. The flowing water carried away sand and dirt and lighter minerals, but a heavier metal was left behind to accumulate in the deepening ditch.

His crew consisted mainly of local Native Americans and veterans of the Mormon Battalion on their way to Salt Lake City, Utah

Construction continued into January 1848, when it was discovered that the tailrace portion of the mill (the ditch that drained water away from the waterwheel) was too narrow and shallow for the volume of water needed to operate the saw. Marshall decided to use the natural force of the river to excavate and enlarge the tailrace. This could only be done at night, so as not to endanger the lives of the men working on the mill during the day. Every morning Marshall examined the results of the previous night's excavation.

On the morning of January 24, 1848, while checking to see that the tailrace of the mill had been flushed clean of silt and debris, Marshall looked down through the clear water below and noticed some shiny flecks in the channel bed.

As later recounted by Marshall:

“I picked up one or two pieces and examined them attentively; and having some general knowledge of minerals, I could not call to mind more than two which in any way resembled this, iron, very bright and brittle; and gold, bright, yet malleable. I then tried it between two rocks, and found that it could be beaten into a different shape, but not broken. I then collected four or five pieces and went up to Mr. Scott (who was working at the carpenter's bench making the mill wheel) with the pieces in my hand and said, "I have found it."

"What is it?" inquired Scott.

"Gold," I answered.

"Oh! no," replied Scott, "That can't be."

I said,--"I know it to be nothing else."

The metal was confirmed to be gold after members of Marshall's crew performed tests on the metal—boiling it in lye soap and hammering it to test its malleability. Marshall, still concerned with the completion of the sawmill, permitted his crew to search for gold during their free time.

By the time Marshall returned to Sutter's Fort, four days later, the war had ended and California was about to become an American possession.

Marshall shared his discovery with Sutter, who performed further tests on the gold and told Marshall that it was "of the finest quality, of at least 23 karat [96% pure]".

Sutter swore all his employees to secrecy.

As Wicks recalled, life just went on as it always had:

"We went to bed at the usual hour that night, and so little excited were we about the discovery that neither of us lost a moment’s sleep over the stupendous wealth that lay all about us. We proposed to go out and hunt at odd times and on Sundays for gold nuggets. Two weeks or so later Mrs. Wimmer went to Sacramento. There she showed at Sutter’s Fort some nuggets she had found along the American River. Even Captain Sutter himself had not known of the finds of gold on his land until then."

As one of Sutter’s employees recounted, "In the latter part of January 1848, I was at work with a gang of vaqueros for Captain Sutter. I remember as clearly as if it were yesterday when I first heard of the gold discovery. It was on January 26, 1848, forty-eight hours after the event. We had driven a drove of cattle to a fertile grazing spot on the American River and were on our way back to Columale for more orders. A nephew, a lad of 15 years, of Mrs. Wimmer, the cook at the lumber camp, met us on the road. I gave him a lift on my horse, and as we jogged along the boy told me that Jim Marshall had found some pieces of what Marshall and Mrs. Wimmer thought were gold. The boy told this in the most matter-of-fact way, and I did not think of it again until I had put the horses in the corral and Marshall and I sat down for a smoke."

Wicks asked Marshall about the rumored gold discovery. Marshall was at first quite annoyed that the boy had even mentioned it. But after asking Wicks to swear he could keep the secret, Marshall went inside his cabin, and returned with a candle and a tin matchbox. He lit the candle, opened the matchbox, and showed Wicks what he said were nuggets of gold.

"The largest nugget was the size of a hickory nut; the others were the size of black beans. All had been hammered, and were very bright from boiling and acid tests. Those were the evidences of gold.

"I have wondered a thousand times since how we took the finding of the gold so coolly. Why, it did not seem to us a big thing. It appeared only an easier way of making a living for a few of us. We had never heard of a stampede of gold-crazy men in those days. Besides, we were green backwoodsmen. None of us had ever seen natural gold before."

The “news” was just too big to keep a secret, and in no time it leaked out, and soon reached around the world.

Mrs. Wimmer's loose lips set in motion what would turn out to be a massive migration of people. One employee of Sutters remembered that prospectors started appearing within months:

"The earliest rush to the mines was in April. There were 20 men, from San Francisco, in the party. Marshall was so mad at Mrs. Wimmer that he vowed he would never treat her decently again.

"At first it was thought the gold was only to be found within a radius of a few miles of the sawmill at Columale, but the newcomers spread out, and every day brought news of localities along the American River that were richer in gold than where we had been quietly working for a few weeks. The very maddest man of all was Captain Sutter when men began to come from San Francisco, San Jose, Monterey and Vallejo by the score to find gold. All of the captain's workmen quit their jobs, his sawmill could not be run, his cattle went wandering away for lack of vaqueros, and his ranch was occupied by a horde of lawless gold-crazy men of all degrees of civilization. All the captain’s plans for a great business career were suddenly ruined."

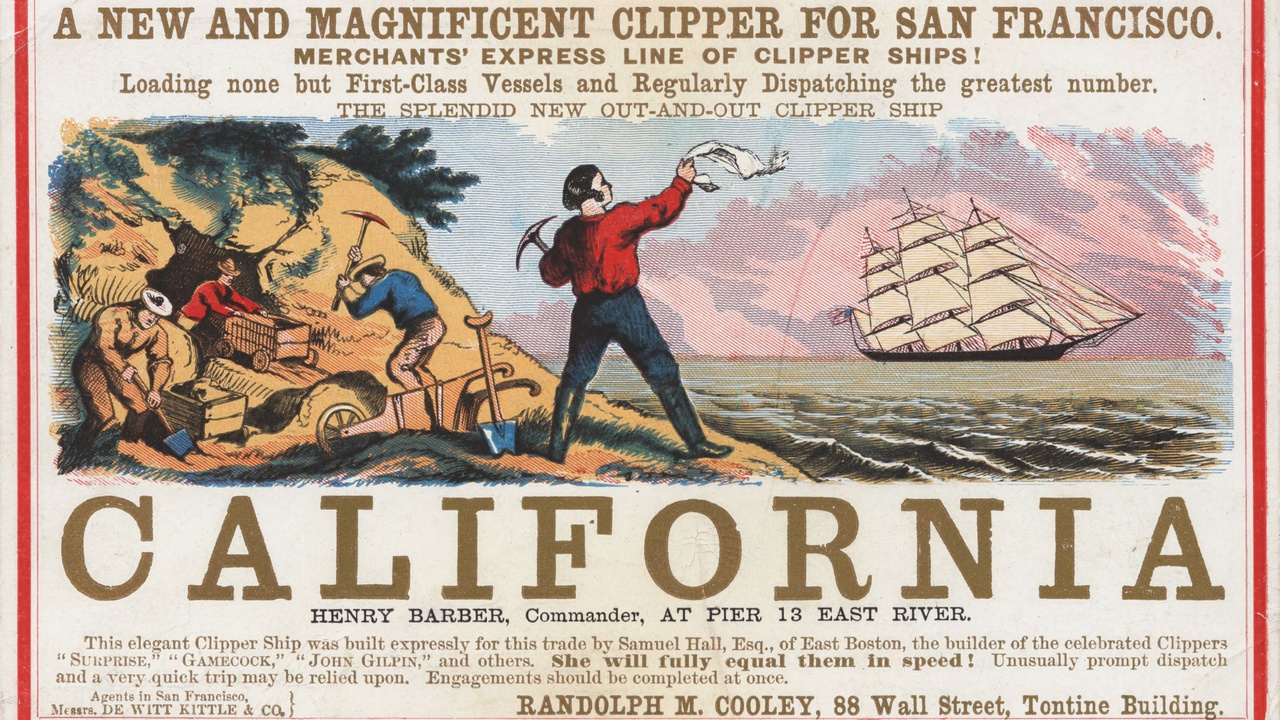

"Gold Fever" soon spread to the east coast, and at the end of 1848, President James Knox Polk actually mentioned the discovery of gold in California in his annual address to Congress. The great California Gold Rush was on, and the following year would see many thousands of "49ers" arriving to search for gold.

Ironically, the subsequent gold rush actually harmed the man who had begun it. Marshall was unsuccessful in securing legal or practical recognition of his own claims in the gold fields, and his sawmill quickly failed when all able-bodied men in the area turned all their efforts to the search for gold.

80,000 miners flooded the area, extending up and down the length of the Sacramento Valley, overrunning Sutter’s domain and forced Marshall off his land.

By 1853 their numbers had grown to 250,000. Although it was estimated that some $2 billion in gold was extracted, few of the prospectors struck it rich. The work was hard, prices were high, and living conditions were primitive.

Neither Sutter nor Marshall ever profited from the discovery that should have made them independently wealthy. Though Marshall tried to secure his own claims in the goldfields, he was unsuccessful.

Marshall bitterly resented his misfortune, but he was helpless to change a course of events he had himself set in motion. He soon left the area.

In 1849, there was a dispute between the native Nisenan and some aggressive gold-miners from Oregon. The dispute turned ugly. Marshall did his best to defend his friends, the Nisenan, but the Indians were murdered and Marshall was forced to flee for his life.

Years later, Marshall returned to Coloma in 1857 and found some success in the 1860s with a vineyard that he started. That venture ended in failure towards the end of the decade, due mostly to higher taxes and increased competition. He returned to prospecting in the hopes of finding success.

He became a partner in a gold mine near Kelsey, California but the mine yielded nothing and left Marshall practically bankrupt.

In what was a typical pattern, the Gold Rush slackened as the most-workable deposits were exhausted and organized capital and machinery replaced the efforts of individual miner-adventurers with more efficient and businesslike operations. Likewise, the lawless and violent mining camps gave way to permanent settlements with organized government and law enforcement. Those settlements that lacked other viable economic activities soon became ghost towns after the gold was exhausted. The California Gold Rush peaked in 1852, and by the end of the decade, it was over.

The California State Legislature awarded him a two-year pension in 1872 in recognition of his role in an important era in California history. It was renewed in 1874 and 1876 but lapsed in 1878. Marshall, penniless, eventually ended up in a small cabin.

Through the rest of his life, he drifted from place to place in California, eventually settling in a spartan homesteader's cabin where he raised a small subsistence garden.

Marshall died in Kelsey on August 10, 1885.

His body was then taken to Coloma and buried on the property where he had owned his vineyard. Overlooking the south fork of the American River, a monument was erected over the grave site in 1890.

In 1886, the members of the Native Sons of the Golden West, Placerville Parlor #9 felt that the "Discoverer of Gold" deserved a monument to mark his final resting place. In May 1890, five years after Marshall's death, Placerville Parlor #9 of the Native Sons of the Golden West successfully advocated the idea of a monument to the State Legislature, which appropriated a total of $9,000 for the construction of a monument and tomb which can be seen today, the first such monument erected in California. A statue of Marshall stands on top of the monument, pointing to the spot where he made his discovery in 1848, and changed California history.

The Gold Rush had a profound impact on California, dramatically changing its demographics. Before the discovery of gold, the territory’s population was approximately 160,000, the vast majority of whom were Native Americans.

Gold spawned a service economy that mined the miners. San Francisco, where the only gold was in the banks, went from a tiny port called Yerba Buena to the 10th-largest city in the United States in only 22 years.

San Francisco popped up, full-grown as a maritime outpost at a time when there was no Denver, no Omaha, and Chicago was just a fort.

It had shootings and lynchings, and San Francisco's streets were mud. But it had culture.

By about 1855, more than 300,000 people had arrived. Most were Americans, though a number of settlers also came from China, Europe, and South America. The Gold Rush was credited with hastening statehood for California in 1850.

Today, California has 33 million people and, although not without its own issues, has an economy bigger than Italy's.

There were the explosions of technology. Californians invented the Pelton Wheel to quadruple the power of water and make hydraulic mining possible. In addition, out of the Gold Rush came Levi's and Wells Fargo, sourdough bread and steam beer, and a sense that California was on the edge; west of the West.

Most of the subsequent accounts of the discovery of gold were fictitious, but it was generally agreed that an old man named Adam Wicks, who was living in Ventura, California, could reliably tell the story of how gold was first discovered in California on January 24, 1848.

The New York Times published an interview with Wicks on December 27, 1897, approximately a month before the 50th anniversary. Wicks recalled arriving in San Francisco by ship in the summer of 1847, at the age of 21:

"I was charmed with the wild new country, and decided to stay, and I’ve never been out of the state from that time. Along in October 1847, I went with several young fellows up the Sacramento River to Sutter’s Fort, at what is now the City of Sacramento. There were about 25 white people at Sutter’s Fort, which was merely a stockade of timbers as a protection from assaults by Indians.

"Sutter was the richest American in central California at the time, but he had no money. It was all in land, timber, horses, and cattle. He was about 45 years old, and was full of schemes for making money by selling his timber to the United States government, which had just come into possession of California. That is why he was having Marshall build the sawmill up in Columale (later known as Coloma). I knew James Marshall, the discoverer of gold, very well. He was an ingenious, flighty sort of man, who claimed to be an expert millwright out from New Jersey."

As Marshall himself would recount, it all started, “One morning in January -- it was a clear, cold morning; I shall never forget that morning -- as I was taking my usual walk along the (mill) race . . . my eye was caught with the glimpse of something shining in the bottom of the ditch. . . . I reached my hand down and picked it up; it made my heart thump, for I was certain it was gold."