D-Day: 75 Years Later

It was 75 years ago today that the largest air, land, and sea invasion in human history began on the shores of Normandy, France.

It was 75 years ago today that the largest air, land, and sea invasion in human history began on the shores of Normandy, France.

It involved 5,000 ships, 11,000 airplanes, and over 155,000 Soldiers, Sailors, Coast Guardsmen, and Airmen. The code name was “Overlord,” and it was the result of years of intensive planning, training, and applied innovation on a scale that’s difficult to fathom even now.

It would prove to be one of the decisive battles and turning points in the war against Adolph Hitler’s Third Reich.

When the doors and ramps opened at dawn on June 6, 1944, many of these Soldiers were not yet 20 years old.

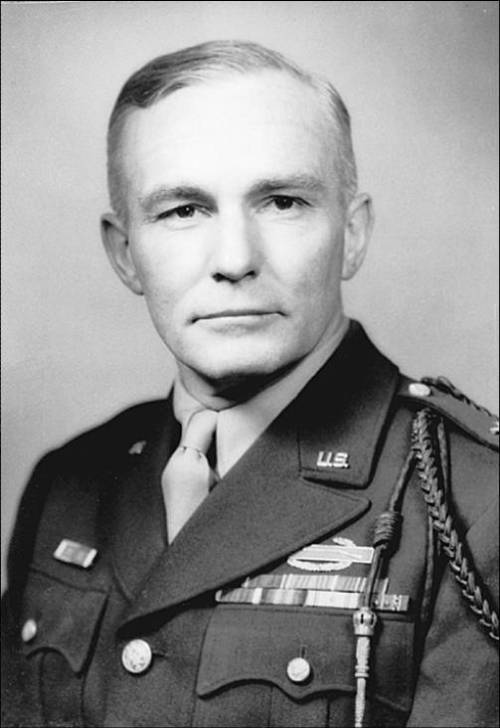

“You get your ass on the beach,” Colonel Paul R. Goode told the men of the 175th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division before D-Day. “I’ll be there waiting for you and I’ll tell you what to do. There ain’t anything in this plan that is going to go right.”

Lieutenant Colonel Robert L Wolverton, who was commanding 3rd battalion, 506th PIR, announced:

Men, I am not a religious man and I don't know your feelings in this matter, but I am going to ask you to pray with me for the success of the mission before us. And while we pray, let us get on our knees and not look down but up with faces raised to the sky so that we can see God and ask his blessing in what we are about to do.

In leading his prayer on behalf of his men, he was as eloquent as he was direct:

God almighty, in a few short hours we will be in battle with the enemy. We do not join battle afraid. We do not ask favors or indulgence but ask that, if You will, use us as Your instrument for the right and an aid in returning peace to the world.

After a moment of silence, Wolverton gave the order, "Move out."

They were carrying well over eighty pounds of equipment on their backs, and they were weakened with seasickness from their extended time on rough seas. The stench of vomit permeated the air.

Some of those men would sink to the bottom under their heavy loads, or be cut down in the shallows, and never step foot on the beach.

Sergeant Ray Lambert, a medic with the 1st Infantry Division, was in the first wave to hit the beach on D-Day.

"The ramp went down, and we were in water over our heads. Some of the men drowned. Some got hit by the bullets. The boat next to ours blew up. Some of those men caught fire. We never saw them again," he said.

Other veterans in the first wave, in other sectors at Omaha, describe an eerie silence at first. They found themselves wondering whether the German defenders had abandoned their positions?

And then, suddenly, a veritable hell-on-earth opened up on Omaha beach, as entire sectors were covered at once with enfilading machine gun, sniper and artillery fire.

Lambert was one of those enveloped in that horrific crossfire. "When we got to the beach, I said to one of my men, Corporal Meyers, `If there's a hell, this has got to be it.' And it was about a minute later that he got a bullet in his head.”

Men from the 1st Infantry Division and 29th Infantry Division were caught in the midst of a kill zone more than two football fields in length that allowed virtually no escape. Friends to their left and right were cut in two, and some were said to evaporate into thin air from pre-planned artillery fire. 200 yards of open beach remained in front of them before reaching natural cover.

The natural human instinct when under that kind of attack is to seek cover. Nothing else. While it's common to talk theoretically about critical decision making in crises, the reality is much different when you're caught in an inferno and surrounded by death.

First Lieutenant George Allen was a member of the First Infantry Division on Omaha Beach. He later described the scene: "All I remember is mayhem--dead bodies floating in the water, busted equipment. We lost a lot of good men that day."

The famous photographer, Robert Capa, was the only journalist to land on the first wave. As he made his way onto Omaha beach, he commented to himself, “This is a very serious business.”

“They’re murdering us here!” Colonel Charles D. Canham, commander of the 116th Infantry Regiment shouted to his men as they struggled on Omaha Beach. “Let’s move inland and get murdered!”

Not far away, Colonel George A. Taylor, commander of the Sixteenth Infantry Regiment, urged his men forward in similar unadulterated fashion. “Two kinds of people are staying on this beach—the dead and those who are going to die!

Inland, and hours previous, paratroopers and gliderborne troops had landed on flooded drop zones and landing zones illuminated by heavy enemy fire from below. Many paratroopers were dead before they hit the ground. Others drowned, tangled and alone in the flooded fields where they landed.

First Sergeant C. Carwood Lipton, a member of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, later confessed, “I took chances on D-Day that I never would have taken later in the war.”

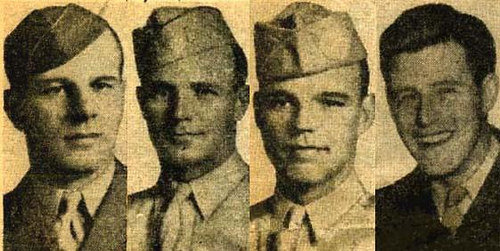

Sergeant Robert Niland, a member of the 82nd Airborne, was killed in the darkness of that early morning. Only a few miles away, his brother, 2nd Lieutenant Preston Niland successfully landed on Utah Beach with the 4th Infantry Division but was killed the next day.

Only one U.S. General participated in the first wave—and that was the Assistant Commander of the 4th Infantry Division, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.—eldest son of President Teddy Roosevelt. Roosevelt realized when they landed that they were far off course of their intended debarkation point. Without hesitation, cane in hand, he nodded and said simply, “Okay. We’ll start the war from right here.”

When it was over, the Allies had suffered 10,000 casualties; and more than 4,000 were dead.

It was personal initiative, combined with good instincts and extraordinary courage--often times by leaders at the tactical-level —who made the right decisions at the right location, at countless critical junctures over the next three months—who made the essential difference on D-Day and in the Battle of Normandy.

Meanwhile, back in Washington, War Department officials were informed that a third Niland brother, Sergeant Edward Niland, had been shot down over Burma three weeks prior to D-Day, and was missing and presumed dead—triggering General George C. Marshal. to direct that Sergeant Frederick "Fritz" Niland--who had parachuted into Normandy on D-Day with the 101st Airborne—be located and extracted from the battlefield without delay. More than a year later, it was a great relief for the Niland family to learn that Edward had also turned up alive after being held captive in a Japanese prison camp.

This story, of course, became the inspiration for Steven Spielberg’s iconic Saving Private Ryan.

A few hours after LTC Wolverton led the prayer for his men, he was killed by German machine gun fire in an orchard outside Saint-Come-du-Mont, Normandy, France. Of the paratroopers in his plane, four others were killed, seven were captured, and three continued the fight.

Brigadier General Roosevelt, already suffering from significant health issues that he kept secret from his superiors, would die from a heart attack only weeks after D-Day, on July 12th, in the vicinity of Sainte-Mère-Église.

These are only some of the stories of D-Day and the bloody months-long battle that followed in Normandy. Others abound, and are only waiting to be discovered and told.

Invariably, words consistently fail to adequately describe the enormous scale of D-Day—but a good place to begin and end any visit to this expansive battlefield is at Normandy American Cemetery. Located on the bluffs of Colleville-sur-Mer, you can stand there at a stone wall, and look down on Omaha Beach and Baie de la Seinewhere hundreds of landing craft dropped their ramps and opened their doors, disgorging thousands of young American GIs who would ultimately never live to see their 21st birthdays. Those who survived would often wonder, “Why me?” Consider, too, as you look down on that beautiful vista, that the Bay of the Seine is also a mass grave. Hundreds of bodies were never recovered from those who were killed outright in the sea.

Now, from where you are standing, turn around and view the sea of white crosses and Stars of David in front of you. It’s peaceful now. Today, children play amongst the crosses; but 75 years ago on this day, it was a savage, horrific battlefield.

The bestselling novelist, Barbara Kingsolver, put it this way:

There's a graveyard in northern France where all the dead boys from D-Day are buried. The white crosses reach from one horizon to the other. I remember looking it over and thinking it was a forest of graves. But the rows were like this, dizzying, diagonal, perfectly straight, so after all it wasn't a forest but an orchard of graves. Nothing to do with nature, unless you count human nature.

Those guns are now silent. And as elusive as words may be to describe the meaning of D-Day today, it is only really possible by citing the values that drove these men in continuing the fight—Personal Courage, Selflessness, Sacrifice, Devotion to Duty, Integrity, Fidelity, Competence, and Honor—all combined to drive them forward in the face of searing images of comrades being cut down, and seemingly impossible odds.

Take the time to visit the graves of our fallen and to learn their stories. There is an extraordinary story behind every one of those headstones.

Seek them out.

Through our veterans’ stories, and by coming to understand the values they convey to us through their own examples, we have been given an extraordinary gift. Our only challenge is to listen.

Year after year following D-Day, former First Lieutenant George Allen, who retired as a farmer in New Jersey, confessed that every Christmas Eve, he would quietly step out of his house to spend time with his fallen friends. "I look up in the sky, and I talk to my men,” he said. “I talk to every one of them.”

General of the Armies John J. Pershing proclaimed, “Time will not dim the glory of their deeds.” And yet, our awareness and understanding of this epic battle—and all others—is slowly, but certainly being defused by the passage of time. It is a great shame, of course, but also a perilous trend—because when we lose sight of the terrible cost of wars in our past, war will inevitably become more easy to wage in the future. It’s our collective responsibility to maintain Pershing’s charge.

On this 75th Anniversary of D-Day, there is no more meaningful—or important—time to learn about this seminal event in world history—and to remember the men and women who played such a crucial role in the liberation of an entire continent.